Now retired, Thomas Chase pursued a dual career as organist and university administrator. In the former role he coordinated the rebuilding of the 1930 Casavant instrument in Holy Rosary Cathedral, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, and in 2004 was named Fellow, honoris causa, of the Royal Canadian College of Organists.

With a longstanding interest in Marcel Dupré and his circle, Chase continues to research and write on French organ literature. Together with his wife Niken Indra Dhamayanti, he divides his time between Vancouver and Jakarta.

Editor’s note: this article was created for the Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and is reprinted here with kind permission of that organization.

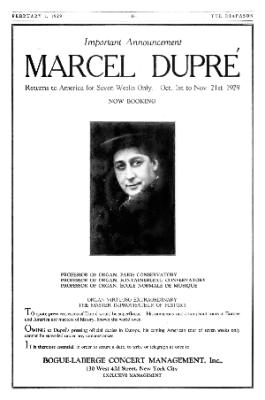

He was, in the words of critic and musicologist Rollin Smith, “one of music’s true immortals,”1 exerting profound influence across the organ world for much of the twentieth century. Yet today, a half-century after his death, Marcel Dupré is a remote figure, his remarkable career unknown to many, and his impact on teaching, composition, performance, and interpretation shrouded by the passage of time.

His legacy of more than 2,100 concert performances, countless broadcasts, and dozens of recordings testifies to his electrifying effect on audiences. From the early 1920s to the day of his death in 1971, Dupré was recorded, broadcast, photographed, filmed, and interviewed in France, the United Kingdom, North America, Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland,

and elsewhere.

Many of these documents are lost. Others, such as the Mercury recordings from the late 1950s that occasioned this essay, have been reissued, in the present case by Decca with the support of Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré in Paris.

Still others, such as his 1948 recording on the Hammond Castle Museum instrument and his English-language interview the same year with radio station WCAL at Saint Olaf College in Minnesota, have resurfaced on platforms such as YouTube and Spotify. In coming years, as they are recovered from archives, more will certainly emerge.

The Mercury recordings of 1957 and 1959 allow us to hear late vestiges of the mastery that from 1912 onward brought Dupré unparalleled plaudits from critics, colleagues, students, and concert audiences around the world. To his teacher Louis Vierne, Dupré was “an artist with absolutely exceptional powers of interpretation, gifted with unrivalled execution.” To his student Olivier Messiaen, he was “the modern Liszt,” “the greatest organ virtuoso ever to exist,” and “a very great composer.”2

Throughout his career, superlatives abounded. The Sorbonne’s Henri de Rohan-Csermak wrote of the “emperor-like image he had gained from his almost half-century reign over the field of the organ.”3 Ely Cathedral organist Arthur Wills declared Dupré “the foremost virtuoso and organist-composer of his time.”4 Rollin Smith argued that “[m]any considered him, as did Widor, the greatest improviser since Bach.”5 And more recently in The New Criterion, critic Nathan Stewart described Dupré as “a genius performer, scholar, and teacher, as well as a composer who bridged the gap between the Romantic and Modern eras.”6

But the truism “time waits for no man” is inescapable. Though Dupré’s Mercury recordings—both those made in America and those made in Paris—together constitute the most substantial range of repertoire he committed to disc, they inevitably reflect his advanced age and most directly the state of his hands. Despite retakes and many edits, slips, split notes, and occasional rhythmic unsteadiness can be heard.

Biographer Michael Murray tells us that in the early 1950s Dupré received devastating medical news. His doctor identified the onset of ankylosis, a hereditary disease of the joints that would cripple his hands just as, decades earlier, it had crippled his cellist mother’s.7 Photographs from late in his life show its effects. By the mid-1950s, his fingers increasingly stiff and gnarled, the peerless virtuosity of his earlier years was constrained. “Through physical incapacity,” wrote Arthur Wills, “the performances of his last years gave little idea of his consummate technique or the superb musicianship so evident throughout most of his career.”8

At the same time, however, the Mercury recordings, comprising more than thirty works by Bach, Franck, Saint-Saëns, Widor, Messiaen, and Dupré himself, affirm that despite his struggles with his hands, Dupré’s interpretive intellect and sheer force of will remained undimmed, as did his rhythmic drive and imperious command of musical line. Above all, Dupré’s performances as captured on these recordings are imbued with a grandeur and nobility that remain uniquely his. Even in his final years, his interpretations and improvisations bore witness to the dictum of his mentor Charles-Marie Widor: “Organ playing is the manifestation of a will filled with the vision of eternity.”9 For today’s readers and listeners, therefore, the following pages offer a biographical overview as essential context for Dupré’s eight Mercury discs from Detroit, New York, and Paris.

1912–1920: Trois Préludes et Fugues, opus 7, the Bach intégrale, and an international debut

In 1912, at the age of 26, Dupré composed his opus 7, Trois Préludes et Fugues. Over the following decades he recorded the third, in G minor, several times, including a 1957 “take” for Mercury at Saint Thomas Church in New York City, forty-five years after he composed it. Though Widor deemed these student works so difficult as to be unplayable, they gave new life to organ composition and performance. Now prominent in the canon of organ literature, they are studied, performed, broadcast, and recorded around the world by organists who possess the technique and musicianship they demand.

In 1914 Dupré won the Premier Grand Prix de Rome in composition for his cantata Psyché on a text by Eugène Roussel and Alfred Coupel. Prevented by the outbreak of war from taking up residence at the Villa Medici in Rome, he remained in France and built up a catalogue of works not only for organ, but also for piano, orchestra, solo voices, and chorus.

Substituting at Notre-Dame de Paris from 1916 onward for his ailing teacher and friend Louis Vierne, Dupré dazzled congregants and visitors with improvisations unlike anything previously heard. (His Scherzo, published as opus 16 in 1920, hints at the dynamism of his improvised works during the Notre-Dame years.) His years at Notre-Dame included many significant occasions, among them the national Te Deum marking the 1918 Armistice. None, however, had the life-altering effect of a momentous encounter the next year, following a cathedral liturgy for which he provided musical responses.

On a mild late-summer afternoon in mid-August 1919, with Vierne still absent from his post as he sought treatment in Switzerland for his eyes, Dupré played the Notre-Dame organ for the service of vespers on the Feast of the Assumption. Dupré’s music for the service was improvised. In the Notre-Dame nave that afternoon was Claude Johnson, managing director of Rolls-Royce. Galvanized by the sounds cascading down the length of the ancient building, the visiting Englishman set in motion a series of events that helped to launch Dupré’s international career. In a January 1921 letter to his brother Douglas, Johnson recalled:

On my first visit to Notre-Dame after the war, it seemed to me that the playing on the big organ was very much better than anything I had ever heard before. . . . On my next visit to Paris, . . . I found seated [at the console] Dupré, whose photographs you have seen. . . .

He was surrounded by some twenty disciples, male and female, mostly pupils, who regarded this young man of 34 years with undisguised awe and admiration. . . . The music flows from his agile hands and feet, which move over the keys and pedals without any apparent effort, like the rippling of a stream overwater around round stones.10

Astonished by the richness and color of Dupré’s improvisations, Johnson resolved to promote the young virtuoso. According to Rolls-Royce historian Tom Clarke, from 1919 onward Johnson “placed company cars at Dupré’s disposal as well as fitting the organ of Notre-Dame (and later Saint-Sulpice) with electric blowers at Rolls-Royce’s expense.”11

Johnson commissioned the London publisher Novello to issue a volume of compositions based on the vespers improvisations. He then arranged Dupré’s international debut. At 8:00 p.m. on Thursday, December 9, 1920, in London’s Royal Albert Hall, before an audience of nearly ten thousand including members of the royal family, Dupré took his bow and sat down at the console. His performance that evening of the commissioned work, Vêpres du Commun des Fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, opus 18, launched a half-century’s touring, performing, broadcasting, and teaching around the world.

As if that were not enough, earlier in 1920 Dupré had astonished the musical establishment with a historic achievement—the first performance of the entire organ œuvre of Johann Sebastian Bach, some two hundred works played from memory in ten weekly concerts. For Vierne, it was “the greatest artistic feat accomplished by a virtuoso since the King of Instruments was first played.” In London, The Musical Times reported:

At the last of these recitals, given before an audience which included members of the Institut de France, many distinguished French musicians and the professors of the Conservatoire, M. Widor addressed the company, concluding with these words: “We must all regret, my dear Dupré, the absence from our midst of the person whose name is foremost in our thoughts today—the great Johann Sebastian himself. Rest assured that if he had been here he would have embraced you, and pressed you to his heart.”12

In subsequent years Dupré repeated the memorized intégrale several times. His concert programs almost invariably featured one or more major Bach works, always played from memory.

1920–1939: “The Modern Liszt”

For Dupré, the 1920s were a decade of intense activity and travel—and enormous accomplishments in performance, composition, and teaching. Extensive tours of Europe and especially of North America earned him both a global reputation and substantial wealth.

With scheduled airline service in its infancy, his tours of the United States and Canada in the 1920s relied on rail travel. A single tour could involve journeys to as many as 110 concert venues spread across the continent. For Dupré, this meant arriving overnight on a sleeper car, preparing and performing a memorized program on an unfamiliar instrument, accepting themes from local musicians for the improvisation of a symphony or other major form, participating with French politesse in a post-concert reception, and then departing for the next city on his tour.

Meeting these challenges required unusual reserves of patience, energy, and intense focus. The reward was fame and fortune unlike anything previously experienced by an organ virtuoso and composer.

His newfound wealth enabled the purchase of a large villa in the Parisian suburb of Meudon. To it he added a 200-seat concert hall or salle d’orgue housing his teacher Guilmant’s Cavaillé-Coll organ, which he later expanded to four manuals and to which he added numerous registrational aids. (These devices were several decades ahead of their time, including sostenutos reintroduced by organbuilders only in the last few decades. Another was the pédale coupure, a device permitting the player to “divide” the pedalboard and assign different registrations to the left and right feet. A generation later, Dupré’s student Pierre Cochereau adopted the coupure in the new console for the Notre-Dame Cathedral organ, where the musical textures it made possible quickly became a key feature of his remarkable liturgical improvisations.)

Supported by Widor, Ravel, and Dukas, in 1926 Dupré succeeded to the professorship of organ at the Paris Conservatoire, assuming the chair earlier held by César Franck and Widor. For the next three decades he taught an unparalleled succession of virtuosi and composers ranging from Olivier Messiaen and Jean Langlais to Marie-Madeleine Duruflé, Jehan and Marie-Claire Alain, Jeanne Demessieux, Françoise Renet, Rolande Falcinelli, Jean Guillou, and Pierre Cochereau. Simultaneous teaching appointments at the École Normale and the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau extended the reach of Dupré’s pedagogy far beyond the borders of France.

Despite the demands of teaching and months-long concert tours, in the 1920s and 1930s Dupré composed works that remain staples of organ pedagogy and concert programs around the world. Among them are Cortège et Litanie (opus 19, number 2) of 1922, Variations sur un Noël (opus 20) of 1923, Symphonie-Passion (opus 23) of 1924, the groundbreaking Deuxième Symphonie (opus 26) of 1929, and in 1939 the magisterial second set of preludes and fugues (opus 36). Like the opus 7 Trois Préludes et Fugues from his student years at the Conservatoire, these works open new vistas of sound for the organ, while advancing keyboard and pedal technique—and making unprecedented demands on performing artists.

1940–1956: World War II, directorship of the Conservatoire, retirement

The German occupation prevented Dupré from touring outside France. He continued to play concerts, compose, and teach at the Conservatoire. On Sundays, together with his wife Jeanne, he walked the five miles from their Meudon home to play services at Saint-Sulpice. His intensive wartime mentorship of the prodigy Jeanne Demessieux deserves (and has received) lengthier discussion elsewhere. Indeed, readers who seek a broader understanding of Dupré’s playing, teaching, and aesthetic are urged to read Demessieux’s diaries in their entirety. They cast a singularly vivid light not just on Dupré, his aesthetic, and his compositions, but also on the bitter rivalries roiling the French organ world in the 1940s.

The following diary entry from Sunday, August 13, 1944, less than two weeks before French and American troops liberated Paris from the Nazis, captures the febrile atmosphere in the city and the effect Dupré’s playing had on audiences. Demessieux writes:

Dupré’s concert at Notre-Dame. Unforgettable . . . 6,500 estimated in attendance. . . . Following the last note, the crowd seemed electrified. . . . The enormous mass of people, leaving the cathedral as a single bloc . . . rushed toward the gate from which Dupré calmly exited. . . . Police officers pushed their way into the middle of the crowd . . . [but] this insatiable crowd would not give him up!13

The war years also saw Dupré write a succession of major works, including the monumental symphonic poem Évocation (opus 37) in 1941, the elegant and approachable Le Tombeau de Titelouze (opus 38) of 1942, and the transcendental Suite (opus 39) of 1944 and Deux Esquisses (opus 41)

of 1945.

After the war ended, Dupré resumed touring abroad. Just weeks after the German surrender, in July 1945 Dupré gave two concerts in London—at the Royal Albert Hall on July 24, and at Saint Mark’s Church, North Audley Street, three days later. The latter concert was broadcast live by the BBC. That his overwhelming impact on audiences remained undiminished can be judged from the following transcript of a verbal account by London-based impresario and critic Felix Aprahamian:

It was at that period that I heard Dupré give possibly the greatest improvisation I ever heard from anyone. The BBC had engaged him to do a broadcast recital on the organ of St. Mark’s, North Audley Street. I remember the organ distinctly, because it had a clock . . . let into the music desk of the console. This was useful for broadcasts because the timing had to be absolutely exact, and Dupré had, I think, until exactly two minutes to eight in which to give his recital. It had to terminate then. And the recital was to end with an improvisation. . . . I’d had Benjamin Britten supply a theme for a prelude and fugue. And it was quite masterly. . . .

When the time came for the improvisation Dupré was handed the theme—two lines—and he looked at them, then he played the theme for the prelude over and then the theme for the fugue. . . . I was particularly interested in what would happen in the fugue because, if I remember aright, it was in C minor and somewhere or other during the course of the subject there was an interval from middle C to the perfect 4th of the F above it, and then down to F sharp in the tenor, followed by A flat.

I mean it really needed a master to instantly light on a counter-subject that would make sense. And he did it. I knew from that moment that this was going to be an absolutely terrific improvisation.

Dupré not only found the counter-subject but this thing unfolded so wonderfully until right at the end—the clock with about thirty seconds to go—a long dominant pedal; we’d had inversions, you name it, every kind of polyphonic contrapuntal device, finally a long stretto maestrale and a glorious C major chord to finish with.14

To Aprahamian’s London account, we add another from Paris by Dupré’s student Bernard Gavoty, music critic of Le Figaro:

One day, in Saint-Sulpice, he improvised “for fun” a ricercare for six voices, with a canon for the middle two—and trained musicians will know what an achievement that represents. Nothing in his face betrayed the effort of an operation which is comparable only with the solution of certain problems in transcendental mathematics.

At the last chord he smiled broadly and, pushing in his registers, said simply, “There! If that is not what one can call genius!” I gasped, astounded and overwhelmed.

Dupré, his face serious again, said suddenly, “Come along!” and, taking me behind the organ to the little room which he uses as a study, he spoke firmly: “Do you know what genius is? I will tell you. Genius is the inimitable find, the harmonic or melodic discovery. It is, for instance, the adagietto in L’Arlésienne, or the first bars of Fauré’s Secret. What I have just given you is an example of a contrapuntal combination, quite difficult to pull off, I grant you, but requiring only a clear head and care in following your voices. . . . I beg of you, stop using big words, and leave genius to the masters!”

His voice as he uttered the words was almost severe, and I went away, determined indeed to leave genius to the masters, on condition that I included in their ranks Marcel Dupré.15

Dupré continued to teach his organ class until 1954, when he assumed the directorship of the Paris Conservatoire prior to retirement at the age of seventy in 1956. The 1950s brought him many accolades including election to the Institut de France, appointment to the rank of Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and an honorary doctorate from the Pontifical Gregorian Institute in Rome.

In addition, he found delight in helping his students assume major posts. Among them was the uniquely gifted improviser Pierre Cochereau, appointed titular organist of Notre-Dame early in 1955. In Dupré’s words, Cochereau was a “phenomenon without equivalent in the contemporary organ world,”16 a status that Dupré himself had enjoyed for decades. In his recent book on Cochereau as improviser, Michel Robert writes:

Barely a month after his appointment, Cochereau was already attracting favourable comment. Among the crowd attending the [February 27, 1955] funeral of poet Paul Claudel in Notre-Dame was composer Arthur Honegger. Listening to the cascades of improvised music pouring down from the organ tribune, Honegger turned to critic and Dupré disciple Bernard Gavoty, and whispered: “But who is capable of improvising like that? It has to be Dupré.”17

1957: A return to the United States: Detroit, New York City, and the Mercury LPs

The year following Dupré’s retirement, his childhood friend Paul Paray reached out from America. Paray, who conducted the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, invited Dupré to play the October 1957 opening concert on the Aeolian-Skinner organ in Ford Auditorium.

Dupré accepted his friend’s invitation, and with the Detroit Symphony recorded Saint-Saëns’ Symphony in C Minor (the “Organ” Symphony) for the Mercury label, helping to launch the era of stereo LP recording. Thomas Fine, who remastered the original Mercury recordings for transfer to CD, is the son of Robert Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine, both of whom were central to the production of the original tape recordings.

During this visit to the United States, he also recorded works by Widor and Franck as well his own Prélude et Fugue en sol mineur (opus 7, number 3) and his Triptyque (opus 51), newly composed for the Detroit visit. To take advantage of a more suitable instrument and acoustic, the solo recording sessions originally planned for the Ford Auditorium were moved at the last moment to Saint Thomas Church in New York City.

On the evening of Monday, October 14, 1957, the Saint Thomas recording sessions began. In her diary, Dupré’s wife Jeanne related that taping was “interrupted every 3 minutes: the microphones pick up a low rumble each time the metro passes under the church. After each recorded fragment, we went to a nearby room to listen . . . allowing us to note anything we were not satisfied with and then resume with a different registration. The process demands a lot of patience.”18

Three days later, early in the morning of Thursday, October 17, the New York recording sessions ended with works by Widor and Dupré. Jeanne Dupré wrote, “We finished just after 2:30 am—with a break for ice cream. Phew! What a relief for Marcel, and what an undertaking!”19

For the seventy-one-year-old artist, it was indeed a major undertaking. During his United States visit, Dupré completed the Saint-Saëns symphony recording, a Detroit solo concert and concert with orchestra, and travel to New York. Then, to fulfil his commitment to Mercury, he undertook three intensive nighttime recording sessions constantly interrupted by the sound of subway trains running under the church in midtown Manhattan.

Listeners will be immediately struck by the imperiousness of Dupré’s readings of his predecessor Widor on the 1957 New York LPs. Before settling into its restrained final bars, the “Salve Regina” movement from Widor’s Symphonie pour orgue No. 2, in particular, reaches a truly disturbing intensity, displaying the “elemental force” so often noted in Dupré’s playing and drawing on the full resources of the Aeolian-Skinner instrument—all captured with dramatic clarity and realism by the Mercury recording team. Of Dupré’s account of “Allegro” from Widor’s Symphonie pour orgue No. 6, Rollin Smith accurately observes that “there has never been a more magisterial performance.” Given the acute problems Dupré was by then experiencing with his hands, it is difficult to understand how he remained physically capable of recording his Prélude et Fugue en sol mineur, opus 7, number 3, at a tempo that challenges young virtuosi even today.

A few hours after the final Mercury recording session ended at 2:30 a.m., Dupré and his wife returned to the church to prepare for his evening concert. After a full day of rehearsal on the Aeolian-Skinner instrument, the Duprés left for dinner. “At 8 pm,” Jeanne Dupré wrote, “we returned to St. Thomas, a stone’s throw from the restaurant. The concert was due to begin at 8:30, but already the vast church was full: on the ground, in the galleries, in the choir section.”20

In his own memoirs, the organist of Saint Thomas Church, William Self, wrote, “Dupré walked to the console as if he had never a care nor a worry, sat down, and started to play—a magnificent recital, fully justifying the expectations of his audience.”21 Jeanne Dupré concluded her diary entry for October 17, 1957 thus: “Words cannot express the grandeur and beauty of this concert. I have never heard Marcel more dazzling.”22

1959: The Mercury recording team travels to Paris

So successful were the New York and Detroit recordings that Mercury signed Dupré to record another five LPs on the instrument that he had played for more than a half-century, the monumental five-manual Clicquot/Cavaillé-Coll organ in the Church of Saint-Sulpice. In late June 1959, Mercury shipped its recording van across the Atlantic. The repertoire by Bach, Franck, Dupré, and Messiaen were recorded in nighttime sessions between July 3 and 12 that warm summer.

Notes taken by the Mercury engineers relate that late in the night of July 9, Dupré finished recording his opus 36 Trois Préludes et Fugues. Earlier that day, the temperature in Paris reached 35.6 degrees Celsius, the highest recorded that year. One can only speculate on conditions inside the recording van, parked outside the church and packed with pre-digital-era recording equipment. Despite the heat outside, the mechanism of the huge instrument and the tuning of its 6,600 pipes remained stable for opus 36, certainly more so than the organ was several days earlier for the Franck and Messiaen recordings. The shepherds’ pipings in Franck’s Pastorale and Messiaen’s Les Bergers, their pitch slightly soured by the oppressive heat, produce an authentically rustic sound!

Less familiar than the 1912 opus 7 Trois Préludes et Fugues, the 1939 opus 36 set makes even greater demands on organists and requires repeated hearings to reveal its riches. Indeed, it is fair to identify these works as an inflection point in twentieth-century writing for the organ. By turns, the three preludes and fugues are gossamer, ethereal, abstruse, playful, sardonic, beguiling, glowing, disquieting, intimidating, and overwhelming.

And as with Suite (opus 39) from 1944 and the Deux Esquisses (opus 41) from 1945, we encounter in opus 36 textures and sounds never before heard in the organ repertoire. Recording these works in the 1980s, Swedish organist Torvald Torén characterized the A-flat prelude and double fugue, opus 36, number 2, as “counterpoint on the level of Bach.”23 Indeed, for many listeners the final pages of the A-flat double fugue are among the finest moments in organ recording, a monument of learned and intricate counterpoint moving inexorably toward a blazing conclusion.

For maximum impact Opus 36 requires not only a large instrument in a resonant acoustic, but a focused effort—physical, interpretive, and intellectual—from the interpreter. Dupré’s July 1959 recording fulfills these requirements with an authenticity that six decades later remains unequalled.

Among the other works Dupré recorded from his œuvre at Saint-Sulpice, especially noteworthy are “Carillon” and “Final” from Sept Pièces, opus 27 (1931). As earlier noted, slips and smudges are evident, Dupré clearly hampered by Saint-Sulpice’s heavy keyboard action during the late-night recording sessions.

But, in both tracks, what moments of magic are to be heard! The “something elemental” in his playing Stuart Archer identified a half-century earlier is very much in evidence here, both in the disturbingly dark underside of the tintinnabulating “Carillon” and the imperious agogic thrust of “Final,” constructed on the B-A-C-H motif.

Turning to Dupré’s 1959 recordings of Bach and Franck, we begin with a necessary understatement. There are many approaches to organ performance, especially when the works of major figures such as these are at issue. The literature is voluminous, the competing pedagogies strongly at odds, and the interpretive factions bitterly and sometimes personally contentious.

Indeed, over the centuries we often witness a new generation reject the aesthetic of its teachers, striking out in new directions. But as history shows, those new directions will in turn be rejected and replaced—not infrequently by a return to the aesthetic of a more distant past.

This essay is therefore not the place to debate the “authenticity” of the seventy-three-year-old Dupré’s performance of Bach and Franck, nor to evaluate competing claims of a “true” tradition of playing Bach or Franck passed down through the generations from teacher to pupil. Neither Bach nor Franck, needless to say, left us recordings that would enable us to verify these claims.

Both, however, taught students who claimed in good faith to have inherited the masters’ manner of playing. Alas, the interpretive approaches of even these first-generation students are often at odds, to say nothing of second- and third-generation successors. Compare, for example, the 1975 recording of Dupré’s works on the FY label by his student Pierre Cochereau to one by Dupré’s grand-student (via Éliane Lejeune-Bonnier) Yves Castagnet on the Sony label in 1993.24 Castagnet provides extremely restrained, literal readings, staying very close to Dupré’s scores and achieving reference-level performances worthy of careful study.

Cochereau’s 1975 recording, on the other hand, makes substantial changes to the score’s indications of tempo, registration, and even rhythm. In his liner notes, Cochereau indicates that Dupré personally gave him approval to make these interpretive changes. Indeed, we know that over the decades even Dupré’s recordings of his own works departed, at times in dramatic ways, from his published scores. Compare, for example, in the Saint Thomas recording his treatment of the closing bars of the Fugue en sol mineur, opus 7, number 3. Dupré shortens the final chords dramatically from the values in the published score—using the Aeolian-Skinner organ’s cohesive attack and the church’s acoustic to generate greater impact, even ferocity.

Harsh things have been said about Dupré’s 1959 Bach and Franck recordings. His critics—among them a number of grand- and great-grand-students of Dupré and his successor Rolande Falcinelli—criticize an aesthetic they hear as dry, metronomic, and anachronistic. These critics also condemn what they see as not only the folly of recording Bach’s masterworks on an instrument far removed from the sound-world of the instruments Bach knew, but also of doing so when playing accurately had become a constant and painful struggle for Dupré.

Today we can leave these conflicts to the dusty corners of organ lofts. Open to Dupré’s aesthetic, a new generation has begun to rediscover musical riches in the Mercury recordings’ emotional restraint, nobility, and deep roots in Dupré’s Conservatoire training with Guilmant, Widor, and Vierne at the dawn of the twentieth century.

We will therefore focus our attention on moments of magic preserved by the Mercury recordings. As listeners will discover, they are both numerous and arresting. Space permits mention of only a few.

Among the Bach works, the Fantasia in G Major, BWV 572, remains to this day a recording milestone. Dupré’s reading of the score turns on its head most, if not all interpretive orthodoxy. Despite a slight unsteadiness in articulation, the flutes of the opening section float serenely out into Saint-Sulpice’s acoustic, garlanding a middle section of five-part harmony that builds—again, contrary to contemporary performance practice—from a gentle opening on the foundation stops through increasingly rich registrations to a massive diminished-seventh chord employing the fiery tutti of the organ’s 102 stops.

As that unstable chord rolls down the nave, the fantasia’s final section begins with serene restraint on a light registration and in a startlingly slow tempo. Together, Dupré’s interpretive gestures magnify rather than diminish both Bach’s musical architecture and the compelling power of this historic recording.

Among the Franck works Dupré recorded at Saint-Sulpice during the July 1959 sessions, Grande Pièce Symphonique and the Fantaisie in A are especially recommended. Here it is appropriate to acknowledge that, for many, the high point of mid-twentieth-century Franck interpretations is the intégrale by Dupré’s student Jeanne Demessieux, recorded for Decca that same month, July 1959, just a few miles away at the Église de la Madeleine.

Indeed, Demessieux’s recording of Franck’s Prière, opus 20 (1862), remains, for many, unequalled in its emotional intensity and sheer poetic beauty. Yet seventeen years prior to the Decca sessions, Demessieux wrote in her diary entry for Friday, June 19, 1942:

Lesson at Dupré’s. I completed all of Franck and the Alkan études today; two sets of scales at maximum speed, after which Dupré said: “That’s unrivalled. . . . What a joy to see you ascend! No one has ever seen something like this.”25

The entry for the following Monday continues:

Morning spent at Meudon to continue the lesson interrupted on Friday. Franck’s 1st and 2nd Chorals. . . . Here is what Dupré said to me today: “Last Friday was staggering for me. . . . Ah! That’s grand, noble; it’s wonderful.”26

We can therefore be sure that Demessieux studied Franck’s works in detail with Dupré. Though remaining at a distance from his prize student’s rhythmic freedom and emotional depth, Dupré’s recordings provide context for her interpretations while presenting listeners with complementary delights. Among these are the adamantine rhythm and at times overwhelming grandeur of Fantaisie, as well as his magisterial traversal of the musical topography of Grande Pièce (which, though differing from Demessieux’s in its musical “feel,” is less than a minute longer—26′ 02′′ versus 25′ 11′′).

Both tracks draw not only on Dupré’s half-century performing Franck in concert on hundreds of instruments worldwide, but also on his experience using Saint-Sulpice’s opulent acoustic to magnify Franck’s musical rhetoric. The result is timeless and irreplaceable accounts of these scores.

In conclusion

When the present decade ends, Dupré’s Mercury recordings from Detroit, New York, and Paris will themselves be more than seventy years old. Yet, now digitized, they will endure well into the future.

Over the years Dupré has inspired countless virtuoso interpreters, composers, teachers, and scholars. They include Graham Barber, Michael Barone, James Biery, David Briggs, Yves Castagnet, Susanne Chaisemartin, Pierre Cochereau, Robert Delcamp, Jesse Eschbach, Rolande Falcinelli, Lynnwood Farnam, Jeremy Filsell, Jean Guillou, Wayne Marshall, Marilyn Mason, Michael Murray, Flor Peters, Françoise Renet, Daniel Roth, John Scott, Rollin Smith, Graham Steed, Stephen Tharp, Torvald Torén, D’Arcy Trinkwon, Ben van Oosten, Clarence Watters, Gillian Weir, Benjamin van Wye, and many more. Their performances and writings are widely available online and via various streaming services.

Now, characterized by a truly impressive interpretive and aesthetic reach, a new generation has engaged with Dupré. Among this diverse international group are the performers, scholars, and teachers David Baskeyfield, Ben Bloor, Katelyn Emerson, Tobias Frank, Pär Fridberg, Vincent Genvrin, Sebastian Heindl, Christopher Jacobson, Jan Liebermann, Angela Metzger, Jean-Baptiste Monnot, Ulf Norberg, Alessandro Perin, Robert Quinney, Jean-Baptiste Robin, and still others. Their performances and writings, many of them available online, are now attracting new audiences to Dupré’s music and aesthetic.

At the same time, moreover, the artistry of this new generation inspires us to revisit a recorded legacy that remains without peer and that will always have much to teach, delight, and move us. The Mercury recordings of 1957 and 1959 form an essential part of that legacy.

Notes

1. Rollin Smith, “Feature Review: Legendary Recordings of Marcel Dupré,” The Tracker, Summer 2017, volume 61, number 3, pages 18–20.

2. Marcel Dupré, Marcel Dupré raconte (Paris: Bornemann, 1972). English translation by Ralph Kneeream, Recollections (Melville, New York: Belwin-Mills, 1975).

3. Yves Castagnet, Marcel Dupré: Symphonies pour Orgue. Sony CD SK 57485, 1993, liner notes.

4. Arthur Wills, “Marcel Dupré” [obituary], The Musical Times, July 1971, page 693.

5. Rollin Smith, “Reviews,” The Tracker, July 2025, volume 69, number 3, pages 43–44.

6. Nathan C. Stewart, “Surpassing Beauty: On the Composer Marcel Dupré and an Organ Concert by Jeremy Filsell,” The New Criterion 44 (September 2025), page 1. newcriterion.com/dispatch/surpassing-beauty/

7. Michael Murray, Marcel Dupré: The Work of a Master Organist. Second ed. (Paris: Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré, 2020), page 192.

8. Wills, page 693.

9. Charles R. Joy, Music in the Life of Albert Schweitzer (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1951), page 168.

10. Unpublished typescript of Claude Johnson’s January 1921 letter from the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, New York City, to his brother Douglas at Manchester Cathedral, page 2, supplied to author by Thomas Murray, who discovered it in the Rolls-Royce archives at Derby, UK.

11. Tom Clark, “Holst in an Unusual Circle,” British Association of Friends of Museums Journal 115 (Winter 2015–2016), page 14.

12. “B,” “Marcel Dupré: The Man and his Music,” The Musical Times 61:934, December 1920.

13. Lynn Cavanagh and Stacey Brown, The Diaries and Selected Letters of Jeanne Demessieux. saskoer.ca/jeannedemessieux/ (cf. also L’Orgue 287–288, 2009).

14. Lewis and Susan Forman (eds.), Felix Aprahamian: Diaries and Selected Writings on Music (Rochester: Boydell and Brewer, 2015). Aprahamian speaks about Dupré: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qu_M0LeQjRo (see 33’ 07”–37’ 37”)

15. Bernard Gavoty, Marcel Dupré (Geneva: Editions René Kister, 1957), page 12.

16. Michel Robert, Pierre Cochereau and Improvisation: A Composer in the Moment. English translation by David Briggs and Thomas Chase (Paris: Delatour France, 2026), page 16.

17. Robert, page 16.

18. Jeanne Dupré, “Trip to America in 1957: Extracts from the Diary of Mme Jeanne Dupré.” Reproduced in Marcel Dupré: the Mercury Living Presence Recordings (Paris: l’Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and Decca Music Group, 2025), page 83.

19. Jeanne Dupré, page 84.

20. Jeanne Dupré, page 84.

21. William Self, For Mine Eyes Have Seen. The Worcester [Massachusetts] Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, 1990, page 175.

22. Jeanne Dupré, page 84.

23. Torvald Torén, Dupré: Symphonie-Passion, Trois Préludes et Fugues Opus 36, Evocation. Proprius PRCD 9003, 1989, liner notes.

24. Pierre Cochereau, Dupré: Organ Works. Solstice CD FYCD 820, 1975; Yves Castagnet, Marcel Dupré: Symphonies pour Orgue. Sony CD SK 57485, 1993.

25. Cavanagh and Brown, page 164.

26. Cavanagh and Brown, page 164. Further confirmation of Demessieux’s study of Franck with Dupré can be found on page 167: “I played all of César Franck, from memory, for the master.”

For suggesting references as well as providing comments on earlier drafts, the author thanks David Briggs, Bruno Chaumet, Thomas Fine, Paul Hale, G. B. Henderson, Mark McDonald, Thomas Murray, and Brenda Righetti. Remaining inaccuracies are his responsibility.

The Mercury CDs discussed in this essay are available from the Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré in Paris, marceldupre.com, order codes 350140-350147. François-Michel Rignol’s CD

of Dupré’s piano works is also available from AAAMD. For information on the recent boxed set including DVD, CD, and booklet, see the second entry below.

Further reading, listening, and viewing

Readers new to Dupré and the Mercury recordings are encouraged to begin their researches with four principal sources: Michael Barone’s invaluable Pipedreams programs on National Public Radio; Tobias Frank’s twelve-part Dupré Digital series on YouTube; Bruno Chaumet’s essay on Dupré; and the second edition of Michael Murray’s biography, available from the AAAMD and the Organ Historical Society (ohscatalog.org).

Archer, J. Stuart. “Marcel Dupré: An Appreciation.” The Organ 2 (1922–1923), pages 6-8.

Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and Decca Music Group. Marcel Dupré: Saint-Louis-des-Invalides. Boxed set including DVD, CD, and 72-page booklet. Available from marceldupre.com, order code 350302. Also available from Organ Historical Society, ohscatalog.org.

“B.” “Marcel Dupré: The Man and his Music.” The Musical Times 61 (December 1920), page 934.

Barone, Michael. Pipedreams (American Public Radio). pipedreams.org. An archive of concert programs and commentary, with numerous episodes on Dupré. Of particular note is program #1618, May 1, 2016. In that episode, Barone converses with Bruno Chaumet, president of AAAMD; audio engineer Thomas Fine, whose parents Robert and Wilma were responsible for the sound of the original 1957 and 1959 recordings; and project consultant Adam Freeman.

Between 1986 and 1999, Barone and his Pipedreams colleagues produced a remarkable eight-part series, “The Dupré Legacy.” It includes programs #8617 (April 27, 1986) with Dupré biographer Michael Murray; #8618 (May 4, 1986); #8633 (August 17, 1986); #8651 (December 21, 1986); #8713 (March 29, 1987); #8718 (May 3, 1987); #9917 (April 25, 1999); and #8819 (May 8, 1988). There is also a “Homage to Dupré” in program #9420 (May 15, 1994) and a complete performance, with plainchant, of the Vêpres du Commun, opus 18, the work that Dupré premiered at London’s Albert Hall in 1920.

Readers will also wish to listen to program #0118 (April 29, 2001), and #1418, (May 4, 2014). In both, Jeremy Filsell, who recorded Dupré’s complete œuvre for Guild, plays and discusses the music.

Baskeyfield, David. Dupré: The American Experience. Acis CD APL67072, 2019.

Castagnet, Yves. Marcel Dupré: Symphonies pour Orgue. Sony CD SK 57485, 1993.

Cavanagh, Lynn. “Marcel Dupré’s ‘Dark Years’: Unveiling his Occupation-Period Concertizing.” Intersections: Canadian Journal of Music 34:1–2 (2014).

Cavanagh, Lynn, and Stacey Brown. The Diaries and Selected Letters of Jeanne Demessieux. saskoer.ca/jeannedemessieux/ (cf. also L’Orgue 287–288, 2009).

Chaumet, Bruno. “Marcel Dupré, 3 May 1886–30 May 1971.” In booklet accompanying the boxed set Marcel Dupré: the Mercury Living Presence Recordings. L’Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and Decca Music Group, 2015.

Clark, Tom. “Holst in an Unusual Circle.” British Association of Friends of Museums Journal 115 (Winter 2015–2016), page 14.

Cochereau, Pierre. Le Point d’Orgue (televised interview from December 1959). youtube.com/watch?v=B__Tac4cxpI&list=RDB__Tac4cxpI&start_radio=1&rv=CBO-fkvztYQ

Cochereau, Pierre. Dupré: Organ Works. Solstice CD FYCD 820, 1975.

Delestre, Robert. L’Œuvre de Marcel Dupré. Editions Musique Sacrée, 1952.

Demessieux, Jeanne. See Cavanagh, Lynn, and Stacey Brown.

Demessieux, Jeanne. César Franck: Intégrale de l’Œuvre pour Orgue. Recorded at the Church of the Madeleine, 1959. Festivo CD 155 and 156, n.d.

Dupré, Jeanne. “Trip to America in 1957: Extracts from the Diary of Mme Jeanne Dupré.” In booklet accompanying the boxed set Marcel Dupré: the Mercury Living Presence Recordings. L’Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and Decca Music Group, 2025.

Dupré, Marcel. Silent film, Paris, 1920. youtube.com/watch?v=Xv3wfbdHQVM

Dupré, Marcel. Marcel Dupré raconte. Bornemann, 1972. Translated by Ralph Kneeream, Recollections. Belwin-Mills, 1975.

Dupré, Marcel. Souvenirs. Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré, 2007.

Dupré, Marcel. Recital at Hammond Castle Museum (Bach, Handel, Franck, Dupré, improvisation on a theme by T. Tertius Noble), August 5, 1948. youtube.com/watch?v=yJnZnaM7E6I.

Dupré, Marcel. Interview at Saint Olaf College, Northfield, Minnesota. November 10, 1948. youtube.com/watch?v=7nqCYH_P5o4.

Dupré, Marcel. The Stations of the Cross, Opus 29. Stephen Tharp, organist. JAV Recordings JAV161, 2005.

Dupré, Marcel. L’Œuvre pour Piano. François-Michel Rignol, piano. Disques FY and DU Solstice/Delmas Musique SOCD 348, 2017. (Available from AAAMD.)

Dupré, Marcel. Piano and Chamber Works. Philip Nixon, violin; Rosanne Hunt, cello; Harold Fabrikant, piano. Toccata Classics TOCC 0755, 2025.

Eschbach, Jesse. “Marcel Dupré: His Legacy Considered 50 Years after his Death.” theleupoldfoundation.org/2022/02/01/marcel-dupre-his-legacy-considered-50-years-after-his-death/

Estang, Flore. “Musicians in the Great War: Marcel Dupré’s Vespers.” Musicologie.org, February 21, 2016. musicologie.org/16/les_musiciens_et_la_grande_guerre_hortus_09.html

Falcinelli, Rolande, et al. “Marcel Dupré: Biography, Technique, Aesthetics, Press Notices.” Musica et Memoria. musimem.com/dupre-bio.htm

Filsell, Jeremy, with Jeremy Backhouse and the Vasari Singers. The Life and Music of Marcel Dupré. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VBdsk7kjr2U. Contains a valuable discussion of Dupré’s career and music by a leading Dupré interpreter and scholar.

Filsell, Jeremy. See also Michael Barone and Nathan C. Stewart.

Fine, Thomas. “Recording Marcel Dupré.” In booklet accompanying the boxed set Marcel Dupré: the Mercury Living Presence Recordings. L’Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and Decca Music Group, 2015.

Forman, Lewis and Susan, eds. Felix Aprahamian: Diaries and Selected Writings on Music. Boydell and Brewer, 2015.

Franck, César. Prière, opus 20 (1862). Decca recording of Jeanne Demessieux playing the organ at l’Église de la Madeleine, Paris, 1959. youtube.com/watch?v=d4SXLLhUcFs

Franck, César. See Jeanne Demessieux.

Frank, Tobias. Dupré Digital: A Man Between the Centuries (twelve episodes). dupre-digital.org

Freeman, Adam. “Marcel Dupré and the [Mercury] Recordings.” In booklet accompanying the boxed set Marcel Dupré: The Mercury Living Presence Recordings. L’Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré and Decca Music Group, 2015.

Gavoty, Bernard. Marcel Dupré. Editions René Kister, 1957.

Hammond, Anthony. Pierre Cochereau, Organist of Notre-Dame. University of Rochester Press, 2012.

Hunt, Donald. “Bach and Dupré: Métrise et Maître” [includes opus 7, number 2, and Dupré’s arrangement of Bach’s “Sinfonia” from Cantata 29. June 12, 2021, concert at Christ Church Cathedral, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. youtu.be/8w-Vwu-jB4Y?t=397

Johnson, Claude Goodman. Letter written from the Ritz-Carleton Hotel, New York, to Douglas Johnson, Manchester, January 5, 1921. Unpublished typescript courtesy of Thomas Murray.

Joy, Charles R. Music in the Life of Albert Schweitzer. Harper and Brothers, 1951.

McDonald, Mark. “The Art of Impossible [includes opus 7, numbers 1 and 3].” June 26, 2021, concert at Christ Church Cathedral, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. youtu.be/Vlejc9Miga8?t=353

Murray, Michael. Marcel Dupré: The Work of a Master Organist. Second ed. L’Association des Amis de l’Art de Marcel Dupré, 2020 (First edition, Northeastern University Press, 1985).

Murray, Thomas. “Claude Goodman Johnson, Patron of Fine Arts and Benefactor of Marcel Dupré.” Organists’ Review 90 (2004), page 354.

Robert, Michel. Pierre Cochereau and Improvisation: A Composer in the Moment. English translation by David Briggs and Thomas Chase. Delatour France, 2026.

Rohan-Csermak, Henri. Notes to Yves Castagnet’s Marcel Dupré: Symphonies pour Orgue. Sony CD SK 57485, 1993.

Self, William. For Mine Eyes Have Seen. The Worcester [Massachusetts] Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, 1990.

Smith, Rollin. “Feature Review: Legendary Recordings of Marcel Dupré.” The Tracker, volume 61, number 3 (Summer 2017), pages 18–20.

Smith, Rollin. An Introduction to the Organ Music of Marcel Dupré. The Leupold Foundation, 2020.

Smith, Rollin. “Dupré in the ‘20s.” Marcel Dupré 50th Celebration. The Leupold Foundation, 2021. theleupoldfoundation.org/2022/02/03/dupre-in-the-20s/

Stewart, Nathan C. “Surpassing Beauty: On the Composer Marcel Dupré and an Organ Concert by Jeremy Filsell.” The New Criterion 44 (September 2025), page 1. newcriterion.com/dispatch/surpassing-beauty/

Tharp, Stephen. Le Chemin de la Croix, Opus 29. Recorded in Saint-Sulpice. JAV CD161, 2005.

Torén, Torvald. Dupré: Symphonie-Passion, Trois Préludes et Fugues Opus 36, Evocation. Proprius PRCD 9003, 1989.

Trieu-Colleney, Christiane. Jeanne Demessieux: Une Vie de Luttes et de Gloire. Les Presses Universelles, 1977.

Vierne, Louis. Mes Souvenirs. Paris: Bulletin de Les Amis de l’Orgue, 1934–1937. Reissued (ed. Norbert Dufourcq) in L’Orgue, 1970.

Wills, Arthur. “Marcel Dupré” [obituary]. The Musical Times, July 1971, page 693.