Matthew Laurence Cloney, born in Baldwin Park, California, in 2000, is an organist currently based in Wichita, Kansas, and is a member of the Wichita Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. From 2014 to 2019 he was organist at several small parishes in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho; he also served in the United States Marine Corps from 2019 to 2024. From 2020 to the present, he has specialized in French organ music of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Gervais-François Couperin (1759–1826) was the last significant member of the famous Couperin family. He was the son of Armand-Louis Couperin (1727–1789) and was organist of the Church of Saint-Gervais-Saint-Protais after the death of his father and brother, Pierre-Louis Couperin (1755–1789), from 1789 to the end of his life. He was also the last organist of Louis XVI, organist of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame (by quarter—four organists rotating every three months—1789–1793), and several other churches in Paris, namely Saint-Pierre de Charonne and Saint-Jean-Saint-François. Gervais-François left numerous works, mostly for harpsichord or piano: sonatas, variations, romances for voice and keyboard, a Symphonie for orchestra, several motets, and numerous organ pieces.

Unlike what the name Couperin would suggest, the music of Gervais-François is far from the style of his famous ancestors, Louis Couperin and François Couperin “Le Grand,” but is much closer to the early Classical style of Mozart, Haydn, and even early Beethoven, and to his French contemporaries, François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829), Louis Adam (1758–1848), Nicolas Séjan (1745-1819), Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier (1734–1794), etc. His daughter, Céleste-Thérèse Couperin (c. 1792–1860), also an organist, succeeded her father at Saint-Gervais from 1826 to 1829. She died childless and in poverty in the provinces, an unfortunate but definite end to the Couperin dynasty.

The organ music of G.-F. Couperin first came to light in 1919 with the publication of an article by Paul Brunold, organist of Saint-Gervais from 1915–1948, “Paléographie Musicale Manuscrits Inédits de Gervais-François Couperin et Armand-Louis Couperin” in L’Écho Musical.1 The article listed twelve autograph manuscripts of G.-F. Couperin with details as to their contents. These manuscripts were most likely among the “small part” of Paul Brunold’s collection that was purchased by the late Nicolas Gorenstein, who published a selection of twenty-nine pieces of G.-F. Couperin in 1997 under Éditions Chanvrelin.2 He also recorded a singular Fugue in E Minor, which did not appear in this edition.3 Until now these autograph manuscripts have been the only known source of G.-F. Couperin’s organ works.

While searching through the collection of the musicologist, François-Joseph Fétis, held in the Royal Library of Belgium, I came across two manuscripts of similar provenance containing sixteen of the twenty-nine published pieces of G.-F. Couperin. Details of both manuscripts are as follows (all texts reproduced are given in the orthography of the original):

Shelf mark: II 3925 Fétis 2166, 374 pages. Title page:

Kirie et Gloria

tout entiers en Plain chant

avec un fleurtis.

pour les Annuels, les Grand Solennels.

les Solennels mineurs, les Double majeurs

les Doubles mineurs, les Semidoubles, et

les Dimanches pendant l’année

Shelf mark: II 3926 Fétis 2167, 428 pages. Title page:

Offices des fêtes et Dimanches de l’annee

pour l’orgue

par Perne

The contents of Fétis 2166 and 2167 generally reflect the title pages—Fétis 2166 contains pieces for the Mass: “Rentrée de Procession,” “Kyrie,” “Gloria,” “Offertoires,” “Sanctus,” “Elévation,” “Agnus Dei,” etc. Fétis 2167 contains pieces for the Vespers and other offices: Magnificats, antiennes, hymnes, etc. Most of the pieces are not attributed, except for a single piece of Josef Seegers (1716–1782 and whose name has various spellings, including Seeger, Seegr, Segert, Zeckert, etc.), a single Fugue of “Grand Charpentier” (Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier, to differentiate from his son, also an organist, Jacques-Marie), several Noëls of Jean-François Dandrieu (1682–1738), and numerous pieces of Justin Heinrich Knecht (1752–1817) from the Vollständige Orgelschule. Several of the suites only mention “de divers auteurs” (of various authors).4

Several suites and pieces are attributable to G.-F. Couperin in that they contain published pieces or they are consistent with the autographs (after the 1919 article and several of the writings of N. Gorenstein). They are as follows:

Fétis 2166: The beginning page of each suite is given as the image number of the digitization, available online from belgica.kbr.be, the pieces appearing in the Chanvrelin edition are followed by the number of the publication order.

Messe pour l’office des petits solennels, Grand Messe en ut [Image 251]: “Grand jeu, fugue,” “Récit de flute,” “Fonds d’orgue,” “Grand jeu,” “Récit de haubois–Polonaise [No. 16],” “Duetto,” “Les flutes & les fonds,”

“Grand chœur”

Messe des petits solennels [Image 263]: “Grand jeu 1e Kirié [No. 6],” “4e Kirié,” “Et in terra,” “Benedicamus te,” “Glorificamus te,” “Qui tollis . . . Suscipe,” “Sanctus,” “Agnus Dei [No. 15]”

Messe des Doubles Majeurs [Image 267]: “1e Kirié,” [3e Kirié], [2e Christe], “7e Kirié,” “Dernier Kirié,” “Gloria in excelsis, en ut,” “Laudamus te,” “Glorificamus te,” “Domine deus rex,” “Domine deus agnus dei,” “Qui tollis . . . Suscipe,” “Quoniam tu solus sanctus,” “Tu solus altissimus &c.,” “Amen,” “Sanctus,” “Agnus dei”

Offertoire [No. 1] (copied from Fétis 2167) [Image 299]

Fétis 2167:

Office pour un Magnificat du 1er ton en ré mineur. Office courant [Image 381]: “Grand jeu,” “Récit de haubois [No. 24],” “Romance [No. 27],” “Deposuit potentes,” “Fond d’orgue,” “Grand jeu [Antienne]”

Magnificat en sol mineur du Second Ton. Office courant [Image 385]: “Grand jeu,” “Récit de haubois [No. 14],” “Triolet [No. 17],” “Bolero [No. 4],” “Fond d’orgue,” “Grand jeu [No. 4],” “Plein jeu”

Magnificat du Sixieme ton en fa majeur. Office courant [Image 391]: “Grand chœur,” “Récit de haubois,” “Triolet,” “Duetto,” “Solo de flute,” “Grand chœur,” “Benedicamus”

Magnificat du 7e ton. En ré majeur. Office courant [Image 395]: “Grand jeu,” “Duettino [No. 21],” “Cromorne avec les fonds [No. 18],” “Les flutes & les fonds [No. 25],” “Fond d’orgue,” “Grand jeu”

Suitte en ré majeur. Fête courante de St. Pierre. [Image 407]: “1er antienne Grand jeu,” “2e antienne,” “3e antienne Fond d’orgue”

Himne pour les 2e vêpres du jour de la St. Pierre. Suitte en sol min. Office courant [Image 408]: “Tandem Laborum, Grand jeu,” “Fuga,” “Fond d’orgue”

Magnificat courant du 1e ton. Suite en ré mineur [Image 409]: “Grand jeu,” “Duo [No. 3],” “Marche [No. 5],” “Les flutes,” “Les mêmes jeux & la montre,” “Grand jeu,” “Plein jeu,” “Benedicamus Grand jeu”

En ut mineur [Elévation] [No. 12] [Image 420]: “Offertoire [No. 1] [423],” “En ut mineur [430],” “Allegro fugato,” “Coriphé & chœur final”

[fragment, Offertoire] [No. 1] [Image 433]

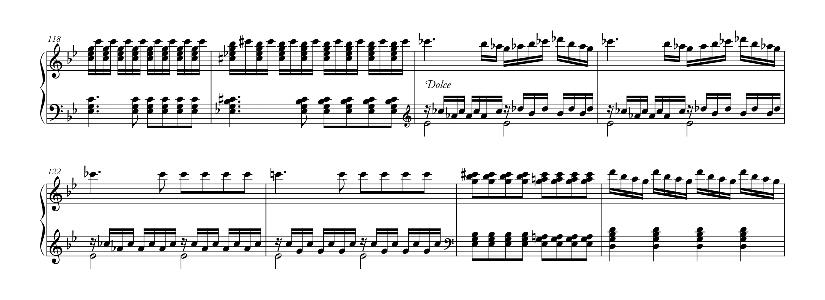

The published pieces that appear in Fétis 2166 and 2167 generally have no significant differences from the published versions. Slurs, articulations, and ornaments have been added to several of the pieces, and repeats were added occasionally, or left out. With one exception (Magnificat en sol mineur du Second Ton, Triolet: “Les fluttes et les fonds” in the Chanvrelin edition, “le clairon, le haubois, et les fonds” in Fétis 2167), the registrations, when present, have not been changed. The ending to the Premier Offertoire, however, has an additional passage to be played on the Positif (see Example 1).

After a thorough examination of the handwriting in Fétis 2166 and 2167, I have identified at least three distinct hands. The first hand, which appears most often, is most likely that of François-Louis Perne (1772–1832) after a comparison to the known autographs in both the National Library of France and the Royal Library of Belgium. The second hand, which appears with some regularity, so far remains anonymous.

The third hand appears very rarely; it includes the Messe des petits solennels, Messe des Doubles Majeurs (Fétis 2166), and the “Benedicamus” in the Magnificat du Sixieme Ton (Fétis 2167). After comparing it to G.-F. Couperin’s autographs in the National Library of France and the facsimiles in the Chanvrelin edition, I am inclined to believe that this hand is that of G.-F. Couperin. Letters with notable characteristics that are identical to the known autographs include (list not exhaustive): uppercase A, D, M, and S, lowercase a, g, r, and s, and most particularly, the final n, r, and s. As for the musical notation, there are several identical elements: braces, key signatures (when more than one accidental is present), half and whole notes, and the paraphs. Further examination of this hand is warranted, but will not be possible until the autographs from the Paul Brunold collection become publicly available.

Fétis 2166 and 2167 are undated; only specific months and days are mentioned for some of the suites corresponding to specific feast days. In the autographs from the Paul Brunold collection, only one date was found: July 4, 1802. The copies in Fétis 2166 and 2167 were presumably made after that date but before the death of F.-L. Perne in 1832.

Comparing suites and pieces listed above to the information given in the 1919 article, numerous correlations can be observed to justify their attribution to G.-F. Couperin. Paul Brunold mentions several corresponding suites: Magnificats of the 1er Ton (Brunold MS 4, following the order given in the article), 2e Ton (Brunold MS 2), 6e Ton (Brunold MS 5), and 7e Ton (Brunold MS 1 and 6), Trois Antiennes (Brunold MS 1), Tandum Laborem (Brunold MS 1 and 2), Messe des Doubles Majeurs (Brunold MS 11), and several Messes des Petits Solennels (Brunold MS 1, 2, and 11).

In the article, only eleven pieces are specifically mentioned (to demonstrate that the autographs were of the same composer since pieces were reused throughout the manuscripts). Several of these most likely correspond to pieces in Fétis 2166 and 2167:

A “fluttes et fonds” for the “2e Christe” in both the Office du jour de St. Pierre (Brunold MS 1) and Messe pour le jour de Saint-Pierre (Brunold MS 2). This corresponds to Messe pour l’office des petits solennels “2e Christe Récit de flute” (Fétis 2166).

“Polonaise” in Office du jour de St. Pierre (Brunold MS 1), page 8 (the context is unknown, given the page number, it is most likely a verset for the Gloria): Messe pour l’office des petits solennels, “Gloria,” “Domine deus rex, Récit de haubois, Polonaise” (Fétis 2166).

“Le triolet” in both Office du jour de St. Pierre (Brunold MS 1) and Magnificat du 6e Ton (Brunold MS 5): Magnificat du 6e Ton, “Triolet” (Fétis 2167).

“Benedicamus” in Office du jour de St. Pierre (Brunold MS 1), Messe du jour de Saint-Pierre (Brunold MS 2), Magnificat du 1er Ton (Brunold MS 4), and Magnificat du 7e Ton (Brunold MS 6): Magnificat du 6e Ton and Magnificat du 1er Ton, “Benedicamus” (Fétis 2167). In the autograph manuscripts, certain pieces were reused; this “Benedicamus” is the only such case in Fétis 2166 and 2167.

Tandum Laborem, 3e verset “Fugue” in Office du jour de St. Pierre (Brunold MS 1): Tandem Laborem [third verset], “Fuga” (Fétis 2167).

Comparing additional details given in Nicolas Gorenstein’s book L’Orgue post-classique français5 and the Chanvrelin edition, there are further points of consistency:

In the autographs, the intonations of the Magnificats (the first versets) are harmonized in the treble, a relatively new process for the organ music of the time, and the plainchants (for the Messe, hymnes, etc.) are harmonized in the bass. All plainchants in Fétis 2166, the intonations for all the Magnificats, the plainchant in Tandem Laborum, and each “Benedicamus” in Fétis 2167 are treated in the same manner.

G.-F. Couperin had a general disinterest in the registration Plein jeu (he had the mixtures at Saint-Gervais removed in 1812), and the autographs rarely indicate it. In the relevant sections of Fétis 2166 and 2167, it is indicated only a few times such as for the “Antiennes” in Magnificat du 2e Ton and Magnificat du 1er Ton (Fétis 2167). In Tandem Laborum (Fétis 2167) the last verset was a Fond d’orgue but was changed to Plein jeu in a different ink. All intonations and plainchants are indicated with Grand jeu instead of Plein jeu when there is any registration indicated.

In the autographs, the plainchants are generally notated in only two voices, the cantus firmus in the bass and a single part above, this is the case in all the plainchants in Fétis 2166, the plainchant in Tandem Laborum, and each “Benedicamus” (Fétis 2167).

The fugues are of a similar case. In the autographs, they are written in an abbreviated manner; the subject entries are notated, but in general only two voices remain, the others were most likely to be improvised. This is the case for all the fugues, Messe des petits solennels, “Grand Jeu, fugue” (Fétis 2166), Tandem Laborum, “Fuga,” and “Allegro Fugato” (Fétis 2167).

G.-F. Couperin was the only composer of the time in France to indicate manual changes in fugues, indicating the Positif and Grand-Orgue. All fugues in Fétis 2166 and 2167 (mentioned above) contain manual indications (see Example 2, page 15).

A final particularity of G.-F. Couperin is the “Coriphé et chœur” (referencing the Corypheus and Chorus of the ancient Greek plays), a dramatic Grand-chœur juxtaposing the Positif and Grand-Orgue. G.-F. Couperin composed two such pieces, though only one was published in 1997. The last piece in Fétis 2167 is a “Coriphé & chœur final,” which is incidentally in the same key

(C minor).

For the end of this study, I have included a transcription of the “Coriphé & chœur final,” written most likely for the organ of the Church of Saint-Pierre de Charonne, a small two-manual instrument without an independent pedal. Like much of G.-F. Couperin’s organ pieces and that of his contemporaries, it requires sometimes numerous additions on the part of the interpreter: addition of a pedal part, modifications to the harmony, addition of missing notes and chords, repetitions ad libitum, and arrangement to take full advantage of the organ at one’s disposition. It is unknown how an organist of the time would have made such “arrangements.” The sources and scores rarely reference such a thing, apart from Nicolas Séjan and one of the anonymous composers of the Livre d’Orgue de Souvigny, who wrote their pieces out to a much fuller extent than their contemporaries, and Josse-François-Joseph Benaut (1741–1794), who states that the pedal part in his pieces is not written because “[the pedal] is one of the first elements of playing the organ, and a trained musician should know Fundamental Bass, and its derivatives.”

For those not accustomed to playing this style of music, there are several suggestions for this piece for an authentic instrument. The pedal part could double the lowest note on the sections for the Grand-Orgue (measures 18–38, 51–54) and the Coda (or a completely different pedal part following Benaut). Chords can be filled in or modified, measures 7–8 can be rewritten to continue the Alberti bass, and in measures 28–32 full chords can be played in the left hand following the harmony and rhythm. On a large enough organ, different manuals can be used, and certain lines can be “brought out.” Measures 1–19 and 47–50 can be played with the left hand on the Récit (up an octave for the shorter compass) and the right hand on the Positif, measures 39–46 can be played on the Écho, most of the sections written for the Grand-Orgue can be played on the Bombarde, measures 50–53 can be played with the left hand on the Grand-Orgue, right hand on the Bombarde. For the Coda, measures 55–58, left hand can be played in repeated eighth-note chords following the harmony, measures 61–64 can be rewritten in syncopated eighth-note chords (c.f. Premier Offertoire, measures 125 and 127), and the Coda can be repeated.

These suggestions are based on my personal manner of playing this piece, so they should not be taken as “definitive.” Gorenstein’s book, L’Orgue post-classique français, and his 1996 recordings, Les Organistes Post-classiques, are excellent resources on this matter. It is recommended for the musician to examine them, experiment with the music, and devise their own interpretations. Ultimately, this manner of interpreting this music can lead to some of the most spectacular results from seemingly uninteresting music, and it is perhaps the most interesting aspect of not only Gervais-François Couperin’s organ music, but also French organ music of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in general.

Notes

1. Paul Brunold, “Paléographie musicale: manuscrits inédits de Gervais-François Couperin et Armand-Louis Couperin,” L’Écho Musical, 4th year, number 3 (July 5, 1919), pages 67–74.

2. Nicolas Gorenstein, ed., Gervais-François Couperin Pièces pour Orgue (Éditions Chanvrelin, 1997).

3. Nicolas Gorenstein, Les organistes post-classiques parisiens (Syrius, 1997).

4. For more information on Fétis 2166 and 2167, including a detailed description and a complete catalogue, an article (in French) is currently in preparation for the journal L’Orgue francophone. A modern edition in three volumes of the music from these manuscripts is also in preparation, the third volume of which will include all the pieces attributed to G.-F. Couperin. This edition will be made freely available on the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP), imslp.org.

5. Nicolas Gorenstein, L’Orgue post-classique français (Éditions Chanvrelin, 1993), pages 61–65.