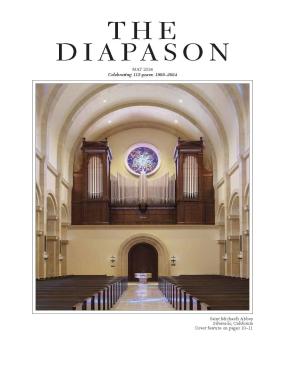

Casavant Frères op. 3837 (2005)

The Brick Presbyterian Church in the City of New York

A brief history of Brick Church’s Casavant organ

Ever since my first encounter with the Cavaillé-Coll archives at Oberlin during my student days there in the early 1980s, it has been a dream of mine to be involved in an organ project that would recreate the sounds of the French symphonic organ in a North American setting. When an anonymous donor came forward to provide funding to replace Brick Church’s long-ailing Austin organ, I knew that the time had come to act upon my dream.

In November 2001, I invited four internationally recognized organ builders from the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, and Germany to bid on a new organ for the Brick Presbyterian Church in the City of New York. I provided the builders with a preliminary specification and design for the organ. The proposed design was strongly modeled after those instruments built in the latter part of the 19th century by the renowned Parisian organ builder, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. Upon reviewing the proposals from these four organ builders, it was particularly telling that three out of the four builders required the assistance of the pre-eminent Cavaillé-Coll expert Jean-Louis Coignet in order to successfully realize this organ. In July 2002, Brick Church commissioned organbuilders Casavant Frères of Ste-Hyacinthe, Québec, for a new electric slider chest organ of 88 independent stops (101 speaking stops), 118 ranks and 6288 pipes. This organ, with its dual sixteen-foot façades, was installed during the summer of 2005.

As Jean-Louis Coignet writes later in this article, tonally recreating a French symphonic organ in the 21st century is not an easy task. Even for a firm such as Casavant with its long history, the techniques of voicing in this style had long departed the firm. After thorough discussion and experimentation with the Casavant voicers, we finally decided upon Jean-Sébastien Dufour, one of the younger voicers at Casavant, to be the head voicer for this project. Mr. Dufour was the most willing and also the most skilled of Casavant’s voicers to realize Dr. Coignet’s explicit directions. Mr. Dufour was assisted in his labors by Yves Champagne, Casavant’s senior voicer. Jean-Louis Coignet, Jacquelin Rochette (when Coignet was in France), and I carefully guided the voicing process both in the factory and at Brick Church.

The Brick Church project was a very detailed and complex one. I am thankful to the trustees of Brick Church for providing the support for me to travel to Casavant on the average of once every four weeks during the construction of the organ. This hands-on oversight allowed for a most exacting and fruitful collaboration with Casavant. In any large organ project, things can develop that are not planned unless there is continuous and careful oversight. I am thankful to André Gremillet, then president of Casavant Frères, who gave me much freedom to interact with the various departments within Casavant. In essence, Mr. Gremillet allowed me to act as their project director for this project. Such collaboration is rare in the organ industry. Mr. Gremillet also allowed Jean-Louis Coignet to realize his dreams and directives in a manner that had not been afforded Coignet previously at Casavant. The scholarly and artistic interaction between Jean-Louis Coignet, Casavant, and myself on all matters involving this instrument made for as perfect a realization as possible.

The Brick Church commission enabled Jean-Louis Coignet and Casavant to realize, without any compromise, a large, new instrument fully in the French symphonic tradition. Dr. Coignet’s life-long, firsthand experience with the great Cavaillé-Coll organs as expert organier for the historic organs of Paris, along with his encyclopedic knowledge of the symphonic style of organ building, have contributed immensely to the success of the organ both mechanically and tonally. The Brick Church organ has few peers in North America in its ability to accurately reproduce the sounds of the great French organs. This organ also holds a special place in the Casavant opus list. It is the last instrument to be completed by Casavant with Jean-Louis Coignet as their tonal director. Upon completion of this organ, Coignet retired from his position at Casavant and also his position as expert organier for the City of Paris.

This organ, a gift of one anonymous donor, is called the Anderson Organ in recognition of the dedicated ministry of The Reverend Dr. Herbert B. Anderson and his wife Mrs. Mary Lou Anderson. Dr. Anderson was senior pastor of Brick Church from 1978 until 2001.

—Keith S. Toth

Minister of Music and Organist

The Brick Presbyterian Church

New York City

Notes from Jean-Louis Coignet on Casavant Frères Opus 3837

Designing an organ in the French symphonic style is by no means a difficult assignment. However, building a new organ today in that style is more challenging as it requires using techniques, particularly of winding and voicing, which have not been in customary use for a long time. Fortunately, there exist a few examples of fine French symphonic organ building that can be carefully studied in order to regain these techniques. These few examples remain, in spite of the many misguided alterations that had been perpetrated during the 20th century on many symphonic organs, especially in France.

As soon as I was consulted about the Brick Church project, I visited the sanctuary and evaluated its dimensions and acoustics as well as those of the organ chambers. At that time I remembered what Cavaillé-Coll had written concerning the location of organs (in De l’orgue et de son architecture): “It is noticeable that the effect of organs is largely lost whenever they are situated in the high parts of a building; on the contrary they profit by being installed in the lower parts. The small choir organs give a striking example of this fact.” So, far from considering it a pitfall to have to put the organ in chambers on both sides of the chancel, I took the best advantage of the situation.

After much discussion with Keith S. Toth, whose clear vision and strong determination were so important all throughout the building of Opus 3837, I realized that the best instrument for Brick Church would be an organ fairly similar to the one built by A. Cavaillé-Coll for the Albert Hall in Sheffield, England in 1873 (this organ was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 1937). Another inspiration came from the organ in Paris’s Notre-Dame Cathedral as I heard it in the mid-1950s. It is a shame that this organ, which was Cavaillé-Coll’s favorite, was completely altered from its original tonal character in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as was César Franck’s Cavaillé-Coll organ in Sainte-Clotilde, Paris.

The Notre-Dame organ displayed a unique sound effect. In no other organ, with the exception of the Jacquot organ in Verdun Cathedral, had the “ascending voicing” typical of the best French symphonic organs been so splendidly achieved. In fact, the main features of the French symphonic organs are:

• a well-balanced proportion of foundation, mutation and reed stops

• huge dynamic possibilities made possible by many very effective enclosed divisions

• voicing of flue pipes with French slots—“entailles de timbre” (different from the Victorian slots used in some Anglo-American organs) and with nicking sufficient enough to prevent any “chiff”

• a winding system that utilizes double-rise bellows

• ascending voicing with full organ dominated by the reeds

Building process of Opus 3837

Specification: The first step consisted in establishing the final specification of the instrument. It was based upon the preliminary stoplist prepared by Keith Toth. The main change from Mr. Toth’s specification was dividing the Grand-Orgue into two parts, Grand-Orgue and Grand-Chœur, in order to gain more flexibility. This is something that Cavaillé-Coll had done in his most prestigious organs. So, the Brick Church organ has actually five manual divisions. The “chœur de clarinettes” in the Positif as well as the various “progressions harmoniques” are features that were typical of the organ in Paris’s Notre-Dame. The Grand-Orgue Bassons 16′ and 8′ were also inspired by that organ, as well as the independent mutations of the 32′ series in the Pédale.

Apart from the stops peculiar to the French symphonic organ, the Brick Church organ offers a few special effects that were not known in France in the 19th century. Three ranks of pipes (Flutes douce and céleste, Cor français) made for the 1917 Brick Church organ by the esteemed American organ builder Ernest M. Skinner, an admirer of Cavaillé-Coll, were placed in the Solo division. We also retained an interesting Cor anglais (free reed stop) made in Paris by Zimmermann in the late 19th century and imported by the Casavant brothers for one of their early organs. The late Guy Thérien, who built the chapel organ at Brick Church, installed this stop in the previous Austin organ. The Récit’s Voix éolienne is another unique stop that only appeared in Cavaillé-Coll’s large organ at St-Ouen in Rouen. This undulating stop is of chimney flute construction for the most part. Its companion stop is the Cor de nuit. With both stops drawn, a slow undulation is heard. This flute celeste has a haunting beauty not found in the flute celestes of the Anglo-American organ.

Pipework: All the pipework was made according to Cavaillé-Coll scalings; metal pipes are made either of “etain fin” for principals, strings, harmonic part of the flutes, and reeds, or “etoffe” (30% tin) for the bourdons. Wood was used for the bourdons up to B 8′. Wood was also used for the large Pédale stops and for the Contre-Bombarde 32′. For reed stops we used Cavaillé-Coll’s typical parallel closed shallots and also tear drop shallots for the Bassons and Clarinettes 16′ and 8′.

Voicing: Much research on the various voicing parameters was done in order to achieve the desired tone: flue width, toe openings, and nicks were measured on a few carefully preserved French symphonic organs. The slotting was particularly well studied. Thanks to documents from the Cavaillé-Coll workshop in my possession, it was possible to recreate the exact tone of the French symphonic “fonds d’orgue.” In his studies on pipes, Cavaillé-Coll documented this matter quite well: the “entaille de timbre” has to be opened one diameter from the top of the pipe. Its width should be either 1/4 of the pipe diameter for most principals, 1/3 of the pipe diameter for strings and some principals, or 1/5 of the pipe diameter for flutes. It should be noted that the harmonic part of Flûtes harmoniques has to be cut dead length and without slotting (though some organ builders used to make slots even on harmonic pipes). As Jean Fellot very correctly wrote: “Slotting had enormous consequences on voicing. It is not exaggerated to claim that this small detail triggered a real revolution.”

Of particular importance in the formation of our voicing goals for Opus 3837 was a visit by Keith Toth, Dr. John B. Herrington III, and me to the unaltered 1898 Cavaillé-Coll organ of Santa María la Real in Azkoitia in the Spanish Basque territory. This three-manual organ with two enclosed divisions was the last instrument completed under the direction of Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, and was voiced by Ferdinand Prince. Immediately upon hearing and inspecting this organ, Mr. Toth and I knew that our voicing goals were well founded and attainable. Moreover, at the same time, I was supervising the restoration of two little-known Parisian organs built in the symphonic style: the Cavaillé-Coll-Mutin (1903) organ in Saint-Honoré-d’Eylau and the Merklin (1905) organ in Saint-Dominique. This enabled me to handle pipes that had not been altered (both organs had escaped the neo-classic furia!), to note their exact parameters and compare their sound to new pipes being voiced.

Winding: Large reservoirs were used throughout, some with double-rise bellows, in order to ensure ample wind supply. The overall wind system is remarkably stable, even when the “octaves graves” are used, but with a subtle flexibility that enhances the instrument’s intrinsic musical qualities. Wind pressures are moderate (from 80mm on the Positif to 135mm for the Solo Tuba), which accounts for the unforced tone of the instrument.

Windchests: Slider chests with electric pull-downs were used for the manual and upper Pédale divisions. The large basses were placed on electro-pneumatic windchests.

Console: Lively discussions and visits with Keith Toth resulted in an elegant console with all controls readily accessible. The console, with its terraced stop jambs of mahogany and oblique stopknobs of rosewood and pao ferro, is patterned after those built by Casavant in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The highly carved console shell is of American red oak and is patterned after the communion table in the chancel of Brick Church. The manuals have naturals of bone with sharps of ebony. The pedalboard has naturals of maple and sharps of rosewood.

Expression: The enclosures are built with double walls of thick wood with a void between the walls. The shades are of extremely thick dimension. These elements allow for the performance of huge crescendos and diminuendos.

Conclusion: Such a complex undertaking would have never been successful without the collaborative spirit that prevailed throughout the process and certainly not without Keith Toth’s determination and involvement. In fact, on many points, he acted as a “maître d’oeuvre”—during the phase of preparation, we had nearly daily phone conversations that were most enlightening. His numerous visits in the workshop as the organ was being built proved extremely useful. It was a great privilege to collaborate with an organist who has such a deep understanding of the French symphonic organ. His absolute resolve for only the very best was most inspiring. It is our hope that this new organ will serve and uplift the congregation of the Brick Presbyterian Church and that, together with the magnificently renovated sanctuary, it will enrich New York City’s grand musical heritage.

—Jean-Louis Coignet

Châteauneuf-Val-de-Bargis, France

Grand-Orgue (I)

1. Bourdon (1–12 common with No. 78; 13–61 from No. 3) 32′ —

2. Montre (70% tin, 1–18 in façade) 16′ 61

3. Bourdon (1–24 wood, 25–61 30% tin) 16′ 61

4. Montre (70% tin, 2–6 in façade) 8′ 61

5. Salicional (70% tin) 8′ 61

6. Bourdon (1–12 wood, 13–61 30% tin) 8′ 61

7. Prestant (70% tin) 4′ 61

8. Quinte (70% tin) 22⁄3′ 61

9. Doublette (70% tin) 2′ 61

10. Grande Fourniture III–VII (70% tin) 22⁄3′ 326

11. Fourniture II–V (70% tin) 11⁄3′ 224

12. Cymbale III–IV (70% tin) 1′ 232

13. Basson (70% tin, full-length, extension of No. 14) 16′ 12

14. Baryton (70% tin) 8′ 61

Grand-Orgue Grave

Grand-Orgue Muet

Grand-Chœur (I)

15. Violonbasse (Open wood, extension of No. 17) 16′ 12

16. Flûte harmonique (70% tin) 8′ 61

17. Violon (1–12 open wood, 13–61 70% tin) 8′ 61

18. Flûte octaviante (70% tin) 4′ 61

19. Grand Cornet V (From No. 20) 16′ —

20. Cornet V (30%/70% tin, from Tenor C) 8′ 245

21. Bombarde (70% tin; full-length) 16′ 61

22. Trompette (70% tin) 8′ 61

23. Clairon (70% tin, breaks back to 8′ at F#4) 4′ 61

Grand-Chœur Grave

Grand-Chœur Muet

Positif (II)

24. Quintaton (1–24 wood, 25–61 30% tin) 16′ 61

25. Principal (70% tin) 8′ 61

26. Dulciane (70% tin) 8′ 61

27. Unda maris (From GG, 70% tin) 8′ 54

28. Flûte harmonique (70% tin) 8′ 61

29. Bourdon (1–12 wood, 13–61 30% tin) 8′ 61

30. Prestant (70% tin) 4′ 61

31. Flûte douce (30% tin, with chimneys) 4′ 61

32. Nasard (30% tin) 22⁄3′ 61

33. Flageolet (30% tin) 2′ 61

34. Tierce (30% tin) 13⁄5′ 61

35. Larigot (30% tin) 11⁄3′ 61

36. Septième (30% tin) 11⁄7′ 61

37. Piccolo (30% tin) 1′ 61

38. Plein Jeu II–V (70% tin) 11⁄3′ 233

39. Clarinette basse (70% tin) 16′ 61

40. Trompette (70% tin) 8′ 61

41. Cromorne (70% tin) 8′ 61

42. Clarinette soprano (70% tin) 4′ 61

Tremolo (Tremblant doux)

Positif Grave

Positif Muet

Récit (III)

43. Bourdon (1–24 wood, 25–61 30% tin) 16′ 61

44. Diapason (70% tin) 8′ 61

45. Flûte traversière (70% tin) 8′ 61

46. Viole de gambe (70% tin) 8′ 61

47. Voix céleste (From CC, 70% tin) 8′ 61

48. Cor de nuit (1–12 wood, 13–61 30% tin) 8′ 61

49. Voix éolienne (From Tenor C, 30% tin, stopped pipes with chimneys) 8′ 49

50. Fugara (70% tin) 4′ 61

51. Flûte octaviante (70% tin) 4′ 61

52. Nasard (30% tin) 22⁄3′ 61

53. Octavin (70% tin) 2′ 61

54. Cornet harmonique II–V (30%/70% tin) 8′ 245

55. Plein Jeu harmonique II–V (70% tin) 2′ 228

56. Bombarde (70% tin; full-length) 16′ 61

57. Trompette harmonique (70% tin) 8′ 61

58. Basson-Hautbois (70% tin) 8′ 61

59. Voix humaine (70% tin) 8′ 61

60. Clarinette (70% tin) 8′ 61

61. Clairon harmonique (70% tin) 4′ 61

Tremolo (À vent perdu)

Récit Grave

Récit Muet

Récit Octave

Sostenuto

Solo (IV)

62. Flûte majeure (1–24 open wood, 25–61 30% tin) 8′ 61

63. Flûtes célestes II (Existing Skinner pipework) 8′ 110

64. Violoncelle (70% tin) 8′ 61

65. Céleste (70% tin) 8′ 61

66. Viole d’amour (70% tin) 4′ 61

67. Flûte de concert (70% tin) 4′ 61

68. Nasard harmonique (70% tin) 22⁄3′ 61

69. Octavin (70% tin) 2′ 61

70. Tierce harmonique (70% tin) 13⁄5′ 61

71. Piccolo harmonique (70% tin) 1′ 61

72. Clochette harmonique (70% tin) 1⁄3′ 61

73. Tuba magna (Tenor C, from No. 75) 16′ —

74. Cor de basset (70% tin, hooded) 16′ 61

75. Tuba mirabilis (70% tin, hooded from CC) 8′ 61

76. Cor français (Existing, revoiced; on separate chest) 8′ 61

77. Cor anglais (Existing, revoiced) 8′ 61

Tremolo (À vent perdu)

Solo Grave

Solo Muet

Solo Octave

Sostenuto

Pédale

78, Soubasse (Stopped wood, extension of No. 82) 32′ 12

79. Flûte (Open wood) 16′ 32

80. Contrebasse (70% tin, 1–18 in façade) 16′ 32

81. Violonbasse (Grand-Chœur) 16′ —

82. Soubasse (Stopped wood) 16′ 32

83. Montre (Grand-Orgue) 16′ —

84. Bourdon (Récit) 16′ —

85. Grande Quinte (Open wood) 102⁄3′ 32

86. Flûte (Open wood) 8′ 32

87. Violoncelle (70% tin, 2–6 in façade) 8′ 32

88. Bourdon (1–12 stopped wood, 13–32 30% tin) 8′ 32

89. Grande Tierce (70% tin) 62⁄5′ 32

90. Quinte (70% tin) 51⁄3′ 32

91. Grande Septième (70% tin) 44⁄7′ 32

92. Octave (70% tin) 4′ 32

93. Flûte (Open wood) 4′ 32

94. Cor de nuit (70% tin) 2′ 32

95. Contre-Bombarde (Wood, full-length, hooded, extension of No. 96) 32′ 12

96. Bombarde (1–6 wood, 6–32 70% tin) 16′ 32

97. Basson (Grand-Orgue) 16′ —

98. Bombarde (Récit) 16′ —

99. Trompette (70% tin) 8′ 32

100. Baryton (Grand-Orgue) 8′ —

101. Clairon (70% tin) 4′ 32

Analysis

Stops Ranks Pipes

Grand-Orgue 12 25 1343

Grand-Chœur 7 11 623

Positif 19 23 1324

Récit 19 27 1498

Solo 15 16 964

Pédale 16 16 536

TOTAL 88 118 6288

Couplers

(Multiplex)

Grand-Orgue à la Pédale

Grand-Chœur à la Pédale

Récit à la Pédale

Récit Octave à la Pédale

Positif à la Pédale

Positif Octave à la Pédale

Solo à la Pédale

Solo Octave à la Pédale

Récit Grave au Grand-Orgue

Récit au Grand-Orgue

Récit Octave au Grand-Orgue

Positif Grave au Grand-Orgue

Positif au Grand-Orgue

Solo Grave au Grand-Orgue

Solo au Grand-Orgue

Solo Octave au Grand-Orgue

Pédale au Grand-Orgue

Grand-Orgue au Positif

Grand-Chœur au Positif

Récit Grave au Positif

Récit au Positif

Récit Octave au Positif

Solo au Positif

Solo au Récit

Solo Octave au Récit

Grand-Chœur au Solo

* Grand-Orgue – Grand-Chœur / Positif Reverse (including divisional combinations)

* This control is not affected by the combination action, crescendo or full organ.

Union des Expressions

Coupure de Pédalier