“To embody music allows you to express the ineffable.” These words spoken by Therees Hibbard, featured clinician for this year’s conference, could easily have served as the conference’s motto. Indeed, embodiment of music was a primary theme of the 2012 National Choral Conference, which began amidst the deepening colors of a Princeton autumn. The 33-member Concert Choir, on risers with the rolling expanse of the Albemarle estate behind them visible through large French doors, began the opening rehearsal in its comfortable manner, although conference participants crowded into chairs, some sitting on the great staircase of the main hall of the school, as an American Boychoir rehearsal, typically devoid of artifice, unfolded. To experience the choir in concert is one thing, in recording another. Yet, to experience the nationally recognized choir in authentic rehearsals is altogether an experience unto itself, especially when the expressive quality of singing becomes subject to bodily motion.

Some regulars to this conference insist that the choir is the conference. Others are drawn to the eminent clinicians, interest sessions, and choral reading sessions. Binding the many strands of a National Choral Conference, however, is the thematic focus upon a particular consideration within the choral art. This year, matters kinesthetic—the relation of body, motion, movement through time and space, and its relationship to vocal production, interpretation and expression—were discussed and experienced. A particular manifestation of bodily motion in the service of the vocal art is called BodySinging: Developing Artistry in Choral Performance, and is the development and specialty of

Therees Hibbard.

Therees Tkach Hibbard is Associate Director of Choral Activities and Associate Professor of Choral Music at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Music. Her work as a movement specialist in the training of choral singers and conductors has created unique opportunities for her to work with choirs and collaborate with conductors from around the world. Her research on enhancing choral performance through movement training has most clearly been demonstrated through her work with the Oregon Bach Festival Youth Choral Academy, the St. Olaf Choir, and with the American Boychoir.

Those familiar with the work of Jaques-Dalcroze may both readily comprehend Hibbard’s work, as well as challenge what may make BodySinging particularly new or unique when compared to Jaques-Dalcroze’s own work in the field of Eurhythmics. Certainly, the incorporation of bodily kinesthetics as a vehicle towards greater musical expression is widely known, notable today in the work of Robert Abramson of the Juilliard School, and recognized as a tool for use within the choral rehearsal by Weston Noble, Andre Thomas, and others.

Similar to the techniques utilized by these practitioners, the American Boychoir and conference participants were themselves challenged by Hibbard to literally step outside of their own comfort zones. Utilizing the space of a large gymnasium, choir and participants were put through a few of BodySinging’s paces. To the accompaniment of preselected recorded music, choir and participants, led by Dr. Hibbard, stepped forward in regular time, arms lifting steadily, coordinated with deep diaphragmatic breathing, followed by relaxation of the same, all movements ordered within the regular pulse of the music, followed by variations and transformations.

This preliminary groundwork forms the basis for the BodySinging principles in their application to the study and supplementation of one’s own vocal work, individually or collectively. This was evident in Hibbard’s incorporation of BodySinging techniques within an open rehearsal of the choir. When, for example, Hibbard desired greater expressivity within a particular musical phrase, she demonstrated kinesthetically what the phrase could look like through her own highly expressive bodily motion. The choir, prompted by Hibbard, then mirrored this motion, followed by a re-execution of the phrase.

Some conference participants responded to the resulting transformation with audible “ahhs” of affirmation. Hibbard explains, “I believe by moving to the music and allowing it to move you, you then can move others.” What makes Hibbard’s BodySinging unique is the specialization and extension of the Jaques-Dalcroze principles as they can apply to the mechanism of vocal production, and ultimately to a fuller realization of emotive possibility. For a full video presentation of Hibbard’s work and the BodySinging principles, go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=IU57HMZwP8I.

As in past conferences, other clinicians presented offerings at this conference, including Helen Kemp, who made a welcomed return. Kemp’s many years of acumen and wisdom in the choral world, as well as her deep humanity, make her appearance at any conference a must see. Her presence was celebrated by unusually extended applause following her presentation entitled “Shaping the Future—One Generation to the Next.” James Litton, another figure of choral gravitas, and Director Emeritus of the American Boychoir, made an appearance with his talk, “Building a Comprehensive Choral Program: The Role of Children Singing.” Dr. Litton was the organization’s music director from 1985 to 2001. Fred Meads, Director of Vocal Studies of the American Boychoir, presented a talk on techniques of engaging in rehearsal the newer members to the school who sing in the school’s Training Choir. Meads exhibited particular gifts in this area in his abilities in training newer choristers. These techniques were demonstrated with enthusiasm in an open rehearsal of the Training Choir. Anton Armstrong, distinguished alumnus and conductor of the famed St. Olaf Choir, gave a talk on working with the developing singer. Lisa Eckstrom, Head of School, presented a talk on the value of arts in education, sprinkled with interesting and relevant data on the changing role of arts in education today. Fernando Malvar-Ruiz, Director of the American Boychoir, utilized individual members of the choir in a presentation to effectively and concretely demonstrate the journey of the changing voice of the boy singer in an effective demonstration of this changing process.

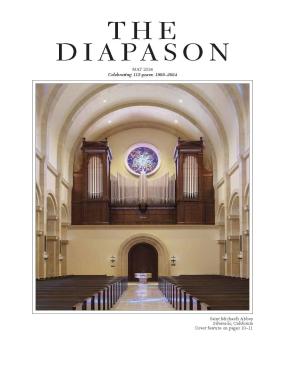

At the conclusion of the last National Choral Conference, Malvar-Ruiz stated, “The next big step in my development as a musician is to embrace the paradigm of a choral ensemble in a 21st-century reality, a 21st-century society, a 21st-century culture” (see “The 16th National Choral Conference,” The Diapason, June 2010). Indeed, the American Boychoir takes a big step towards a new paradigm as choir and school take up residence in their new home at the newly created Princeton Center for Arts and Education (PCAE), formerly St. Joseph’s Seminary in Princeton. Founded in 1912 by the Congregation of the Mission (the Vincentian Brothers) to train young men in the priesthood, the all-boys high school closed its doors in 1992. Since then, the Board of Trustees for the American Boychoir negotiated a long-term lease for the former seminary, whose facilities consist of an impressive set of gothic-revival buildings surrounded by over 45 acres of land.

In the words of Chester Douglass, board chairman of the American Boychoir, the school has “gained a beautiful new campus with expanded facilities such as a gymnasium and a performance hall that were missing at Albemarle. But an equally exciting part of the plan from its beginning was to be the leading resident organization on a shared campus that emphasized the arts within an academic education. Accordingly, we have invited other schools and arts organizations to be part of a greater whole.” Those other two resident organizations include the Wilberforce School and the French American School of Princeton, also joining the campus.

The buildings are to be occupied by the boys and the school as the American Boychoir continues to be one out of only two remaining choral boarding schools in the country (the other being St. Thomas Choir School, New York City, a mere 50 miles to the northeast). For information, go to www.americanboychoir.org.

In a sense, the conference had one foot set in the old school at the Albemarle campus, and the other foot set in the new. During a tour of the new campus conducted by Kerry Heimann, accompanist for the American Boychoir, participants were shown, in his words, the “crown jewel” of the new buildings: the resplendent chapel of the former seminary. The chapel boasts genuine and soaring gothic lines, collegiate-style choral stalls, and opulent acoustics, and will serve well as the long and much-needed regular venue for American Boychoir concerts when the choir performs at home. School and choir begin a promising new journey.

New facilities aside, what is an element that will secure the future and promise of the American Boychoir? In the words of Christie Starrett, General Manager of the American Boychoir, “What makes it special are the boys, without question, and there is a sense of community you cannot find literally anywhere else.”