Industrial hygiene

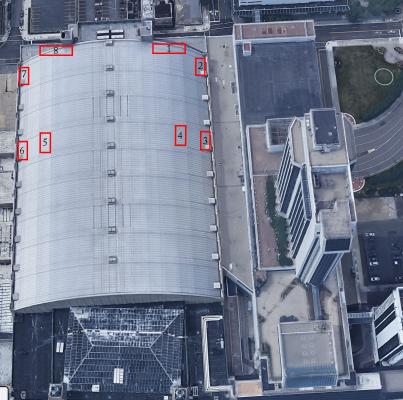

Photo caption: Boardwalk Hall showing the locations of organ chambers and the adjacent Trump Hotel: 1, Right Stage chamber: Great, Solo, Solo-Great, Grand Great, Pedal Right; 2, Right Forward chamber: String II, Brass Chorus; 3, Right Center chamber: Gallery I, Gallery II; 4, Right Upper chamber: Echo; 5, Left Upper chamber: Fanfare, String III; 6, Left Center chamber: Gallery III, Gallery IV; 7, Left Forward chamber: Choir; 8, Left Stage chamber: Swell, Swell-Choir, Unenclosed Choir, String I, Grand Choir, Pedal Left. (photo credit: Historic Organ Restoration Committee)

In this year of Covid, we have stepped up our personal hygiene. We are wearing masks, avoiding crowds, and not touching public surfaces. We are reciting the alphabet or the Lord’s Prayer while washing our hands. In an earlier column, I suggested the famous hand-washing lines from Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking scene, “Out, damned spot! Out, I say!” If you recite it with feeling, you can easily get twenty seconds from it. A meme suggested, “I’ve used so much hand sanitizer that the answers to my eighth-grade social studies test appeared on my wrist.”

Over forty-five years of working on pipe organs, I have used the words “industrial hygiene” to describe how a congregation keeps its buildings. A few years ago, I visited a church in the Pacific Northwest where the rector told me that when he started his ministry there, every nook and cranny was stuffed with junk. He spent a lonely late evening walking through the building, looking into closets, desk drawers, kitchen cabinets, and mechanical spaces, determined to remove anything unneeded to reclaim usable space in the valuable building.

With the support of the vestry and lots of volunteer labor from the members, dumpsters were loaded with the detritus of years of neglect, cabinets were scrubbed, and closets were painted. New ministries were developed, and by the time I visited the place, the building was neat and clean and bustling with all sorts of activity.

This topic comes up in these pages occasionally, typically inspired by the current flow of work of the Organ Clearing House. Loyal readers will recall the organist who called in a panic on a Saturday as a wedding was about to start and the organ wouldn’t. I bolted to the church, walked through the throng of limo drivers, bagpipers, bridesmaids, and groomsmen to the cellar stairs under the organ and found a card table sucked up against the blower intake.

I served a large church in a suburb of Boston as director of music. When I went to the church to audition for the position, I noticed that the stalls in the men’s room were wobbly. They were still wobbly when I left the position seventeen years later. Two years ago, we installed an organ in a small church in rural New Jersey. The building was about thirty years old, attractive and simple, but I was most impressed by the beautifully furnished and equipped restrooms. After decades of experience with crumbling facilities in aging buildings, this made the job much more pleasant. When I commented on this to the pastor, he told me that he was disappointed in the condition of the restrooms when he arrived and thought the good people of the church deserved better. That is a nice way for the church to welcome you.

In one church, we had to climb an iron ladder and walk across the attic to reach the door of the organ chamber. The life-sized plywood cut-outs that formed the Nativity scene for the front lawn were in the attic, and there was the manger, the size of a baby’s crib, laden with a hay bale with a wisp of smoke curling toward the ceiling as its innards decomposed. I lugged it down the ladder to the hallway, went to the office to report it to the secretary, and left the building for lunch. When I came back an hour later, the hay bale had been dutifully returned to the attic. I am pretty sure there would have been a fire if I did not drag it down again, this time outside to the driveway.

Going for the first time to a church with a large organ, I went to the basement to inspect the blower. There was a big old Spencer Orgoblo safely ensconced in a fireproof enclosure that was chock full of junk: a four by eight plywood sign announcing the 1968 church fair, some baby carriages that I supposed failed to sell in 1968, boxes of books, and a hanger rack festooned with abandoned choir robes. Another organ is out of tune, and by the sound of it, we figure there is something wrong with the wind pressure. Yup, a stack of folding chairs lying on the reservoir. That will do it.

Protection

An extension of the importance of good building hygiene is the care of the organ when contactors will be raising dust around the instrument. If you get wind that the people of your church are thinking of any sort of renovation inside the sanctuary, it is important to be sure that the well being of the pipe organ is part of the plan. Your organ technician should be involved, consulting with contractors to establish the extent of protection. Common precautions include:

• putting Ziploc® baggies over the tops of reed resonators, or if the planned work is extensive and extra messy, removing the reeds from the organ and packing them in crates;

• disconnect any expression actions so the shutters can be fastened in the closed position;

• cover any exposed divisions with at least two layers of plastic (so the dirty outer layer can be removed without dumping debris onto the pipes);

• cover an organ case with at least two layers of plastic, taping the seams to be airtight;

• build a sturdy framed box over a detached console, because you know those painters are going to stand on top of it no matter what you say. Remove the pedalboard and bench to safety;

• disconnect power to the blower so it cannot be turned on inadvertently and suck all that nice dust into the organ’s internal mechanisms. Cover the blower air intake with plastic taped firmly in place;

• inspect every area that contains organ components and take appropriate measures;

• be sure not to allow contractors to remove any of this equipment. They will protest that they will be careful, but they will not know the degrees of sensitivity of the instrument. All work relating to protecting the organ should be accomplished by a professional pipe organ company.

This work is expensive, time consuming, and can be inconvenient. In September of 2020, the Organ Clearing House covered a large, new freestanding mechanical-action organ to protect it while the sanctuary was painted. The painting was to be completed so the organ could be recommissioned in time for Christmas. It was completed in mid-December, but because of Covid-related travel restrictions, it would not be possible for the organ to be playable until early February. It was an immense disappointment for all involved, especially considering that this would be only the second Christmas for the new organ. But the valuable and mighty, yet delicate instrument was preserved safely from invasion. Had the organ not been protected, the long-term effects could hardly be calculated. Reed pipes would no longer tune or speak reliably. Adjustment of the action would be compromised. The console cabinet would certainly have been damaged (it is an awful sight to see a drawknob snapped off), and the sound of the flue pipes would have been dulled by accumulation of dust in their mouths. If dust had made its way into the wind system, abrasive dust would speed the deterioration and corrosion of sensitive action parts.

This summer, the Organ Clearing House will clean an organ that was not protected when the ceiling and walls of the nave were sanded and painted, the floor was sanded and refinished, and carpet runners on three aisles were torn up and replaced. Our project will include removing and cleaning all the pipes, vacuuming and polishing the case, dismantling the keydesk to remove abrasive dust from keyboard bushings, cleaning windchests, and “flushing” out the wind system. The façade pipes have elaborate stenciling, recently restored, thus requiring special handling. This work will be exponentially more expensive than covering and protecting the organ before the start of building renovation. And while we have techniques and protocols for handling organ pipes and components with care, partially dismantling the organ will upset its stability so that it will take time after reassembly for the organ to settle down tonally and mechanically.

Water works.

In early January, a water main broke on Lexington Avenue in New York City, and a neighboring church was flooded. Lower-level offices and meeting spaces showed high-water marks on walls and furnishings. Music libraries and filing cabinets were submerged, along with all the trappings and equipment you would expect to find in a busy Midtown church. Only an inch or so of water stood on the floor of the sanctuary, so the free-standing pipe organ was not directly affected, but the amount of moisture introduced inside would necessitate a vigorous, invasive cleaning process. The only way to protect the organ from the remediation was to remove it from the building, and because of the importance of getting the cleaning under way as soon as possible, the organ would be removed immediately. The speed at which that decision was made was a tribute to the commitment of the parish to its organ that is now safely in storage with no schedule established for its return.

Thar she blows . . . .

Atlantic City, New Jersey, is on the southern Jersey shore in an area of rich farmland and state forests. It is about fifty miles north of Cape May, the southern tip of New Jersey that juts out into Delaware Bay, and 125 miles south of New York City. The state’s coastline is famous for beaches, summer bungalows and mansions, shellfish (especially crabs), and boating, but only Atlantic City is a mecca for gamblers. The city is home to nine full-fledged casinos, gaudy complexes with huge hotels and restaurants, high-end shopping, performance spaces, and, of course, acres of gambling floors with armies of one-armed bandits, blackjack, craps, and roulette tables, and (no doubt) secret back rooms where bad things happen.

The city’s waterfront sports a famous boardwalk above the long beach where gamblers can celebrate their winnings, or more likely lament their losses. It is lined with ice cream and salt water taffy shops, al fresco dining, souvenir vendors, and all the hustle-bustle you would expect to find at a popular seaside resort. And there are two immense pipe organs, one of them simply as big as they come.

Boardwalk Hall is perhaps best known as home to the Miss America Pageant—“There she is, Miss America . . . .” It is a capacious place with more than 10,000 seats built in 1929, large enough to have hosted the first-ever indoor college football game and indoor helicopter flight. It has been host to political national conventions (Lyndon Johnson was nominated as the Democratic candidate there), concerts, and even rodeos. And it is the home of the world’s largest musical instrument, the mystical, magisterial, mammoth Midmer-Losh organ with 449 ranks over seven manuals and a total of 33,112 pipes. You can see the bewildering stoplist in the November 2020 issue of The Diapason, pages 1, 14–20, and at boardwalkorgans.org.

Over the last several years, the Historic Organ Restoration Committee has undertaken the painstaking, mind-boggling restoration of the Boardwalk Hall organ and the large Kimball organ in the adjoining 3,000-seat Adrian Phillips Theater. The curatorial staff, assisted by volunteer organ builders, has been methodically moving from one chamber to the next, bringing the long dormant instrument back to life. Nathan Bryson, the organ’s curator, told me that 238 of 449 ranks (about 53%) are now in restored and playable condition.

The mammoth console is in a decorated cylindrical booth at the right of the stage. It towers over people standing next to it and looks like a D-cell battery from the other end of the room. The console booth has doors that close to protect the keyboards and hundreds of stop tablets. Nathan told me that the last time there was an indoor car race, there was a wreck and a chunk of a rubber tire slammed into the doors. Good thing they were closed. Indoor car racing? If we are used to worrying about protecting an organ from some contractor’s dust, how can you protect eight big organ chambers from an automobile race? Nathan explained that they close all the expression shutters (there must be thousands), and run fans inside the chambers blowing outwards to inhibit the influx of dust. It is all in a day’s work when you are caring for the largest organ in the world.

Nathan and his staff faced a challenge larger than indoor car racing and rodeos. On February 17 (Ash Wednesday), just after 9:00 a.m., the neighboring Trump Hotel, part of the Trump Casino complex, was demolished by implosion using 3,000 sticks of dynamite. Years ago, I maintained a small organ that was at the “street end” of a church directly across from the town’s library, the same organ with the card-table wedding. The town had built a sorry addition to the library in the 1950s that was to be demolished. I learned about the event through an emotional call from the organist. Shock waves from the blast had wrecked the organ’s tuning. It was not such a big deal, it was a small organ with everything easy to reach, but when I first read about the intention to demolish a high-rise hotel with over 900 rooms, I wondered about the safety of the organ.

Boardwalk Hall is immediately adjacent to the casino complex, the windows of the organ workshop look directly at the three-or-four-story casino, about two feet away. The hotel was on the other side of the casino. A year before the event, representatives of the demolition company toured the hall and the organ. Overseas shipping containers were stacked outside to protect the hall from falling rubble. To control dust during the implosion, windows and doors were sealed with plywood and plastic, HVAC ducts were sealed with plastic, and organ chamber doors were sealed with plastic, towels, and sandbags.

The Echo division in the Right Ceiling Chamber (#4) would be closest to the action. Lacking the funding to remove the division to safety, Nathan and his staff removed the 16′ Basson, an exceedingly rare stop built by Welte with free reeds and papier-mâché resonators, and they took sample pipes from the other ranks so that they could be reconstructed if damaged.

The staff had learned earlier about the presence of dust in the building when a high-pressure wind line burst off its flange and raised enough dust to set off the building’s fire alarms. As the time of the implosion approached, they set up a video camera to record the event in the hall. Officials cleared the building, and the hotel fell, cheered by the large crowd that had gathered. Videos of the event blanketed the internet. If you are interested in watching it, you’ll have no trouble finding it.

At 11:15 a.m., the staff received the “all clear” notice to reenter the building. When they viewed the video, they were able to see a slight wave of dust move across the hall, enough to worry an organ curator, but nothing like a rodeo or car race.

Congratulations to Nathan Bryson and his staff of four full-time and two part-time technician/restorers for bringing that mighty organ through disruptive events like no other. I encourage you to visit the website to read about the unique instrument, follow the progress of the restoration, and if you choose, click the “Donate Now” button on the home page. They still have 211 ranks to go, five times the size of what we would call a good-sized organ.