June 2, 2014

23Mar 2014 Ciampa_Nosetti tribute.pdf

By Leonardo Ciampa

Massimo Nosetti was one of the busiest organists in Italy. Born in Alessandria, Italy, on January 5, 1960, he studied organ, composition, and choral conducting at the conservatories of Torino (Turin) and Milan. He then studied in Switzerland with Pierre Pidoux and in France with Jean Langlais. He was a professor of organ and composition at Cuneo Conservatory from 1981 till his death, and was titular organist of the cathedral in Torino (home of the famous shroud). At the Basilica di Santa Rita in Torino, where he was the long-time director of music, he was responsible for the installation of a splendid four-manual tracker by Zanin, one of the finest organs in the region.

It would be impossible to list all of the cities in which Maestro Nosetti played concerts, gave masterclasses, and recorded CDs. He also found time to teach, compose, and serve as a member of the Diocesan Commission of Sacred Music and as a consultant of the National Commission for Sacred Music. From 1999 to 2004, he was also vice-president of the Italian Association of St. Cecilia; at the time of his death he also served as dean of their organ department.

On November 12, I received an e-mail entitled, “RIP Massimo Nosetti.” I thought it had to be a mistake, some sort of misprint. How could Massimo be gone? He was only 53 years old. I never heard a word about his being sick. A colleague of mine in Torino said, “That’s not possible. I heard him play a Mass in the cathedral just last month; he looked fine.” Alas, it was pancreatic cancer, noted for its swiftness. As I later learned, the tumor was discovered late the previous September, less than two months before his death.

It was hard not to think about Massimo for the rest of that day. Every time I thought of him, the word that came to mind was “impeccable.” He dressed impeccably, spoke impeccably, played the organ impeccably, interpreted music impeccably. And he was an impeccable friend. If I wrote to him, he wrote back. If I asked him a question, he answered it. His high standards did not require condescension as part of the package. In fact, I think condescension was foreign to his nature.

Upon receiving the sad news, many people wrote about the similarities between Massimo the organist and Massimo the person. He was always well groomed and well dressed; you couldn’t picture him without a tie. He was a serious person, yet he was always approachable—never cold, never inhuman. He had wonderful taste, but instead of being snobbish about it, he was pragmatic. I remember, for instance, one night near Boston, when we were deciding what to have for dinner. I was nervous, because there were no “Italian” restaurants around that would have had food that he would have recognized. But he said, “You know what I’d really like? A nice steak!” He knew that steak was something that Americans did well. In his mind, steak was not “inferior” to gnocchi. Authentic steak is certainly superior to inauthentic gnocchi.

Impeccable, well groomed, serious, tasteful, pragmatic, approachable, never cold or snobby, always striving for authenticity—these, indeed, are traits that could be used to describe his playing. In 2004, he played an unforgettable recital at St. Paul’s Church in Brookline, Massachusetts. Entitled “From the Classic to the Neoclassic,” the concert was a survey of Italian organ music from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. The instrument was a two-manual organ in a room seating only 200 people. From the first notes he played, he grabbed my attention with phrasing and lyricism that made me think the room was five times its size—grand but never dragging, elegant but never cool. Stylistically, every piece was beyond reproach. He elevated the repertoire, the organ, even the acoustics to his own high standards. Yet it never felt like an academic experience, but rather like a person communicating music to an audience. It was music-making of the highest order—all the more impressive because the repertoire contained no “masterpieces.” (This wasn’t Bach’s Passacaglia or Franck’s A-minor Choral.)

Even the greatest organists sometimes have an off night. Yet you just never heard about Massimo ever playing a recital, or even a piece, that wasn’t up to snuff. And he played everywhere. He played concerts in every part of Italy, in every country in Europe, in the United States, Canada, Mexico, South America, Russia, Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Australia, and New Zealand. His vast repertoire included the complete works of Frescobaldi, Buxtehude, Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Franck, Hindemith, Alain, and Duruflé.

Massimo hosted my very first concert in Italy. I had dear friends who lived in Torino near the Basilica di Santa Rita. From the first time I set foot in the special ambience of the basilica, I dreamed of playing there one day. Massimo allowed this dream to become a reality. It was during his tenure that the basilica purchased a wondrous instrument by Zanin, built in 1990—a four-manual tracker, very unusual for Italy! But it was more than just the instrument. It was the magic of the piazza, the magic of the basilica that dominated it, the magic of getting to play my first recital ever in Italy . . . and the magic of Massimo Nosetti, the gentleman who was the reason it all was happening.

Massimo was a faithful, confident man who, at the same time, took nothing for granted and made no assumptions. Every note he played, every lesson he taught, every aspect of every project he embarked upon—everything counted.

Massimo Nosetti had colleagues and friends throughout the world. This tribute is merely a tiny token of the impression that he made in Italy and France. I translated the Italian reminiscences; the French reminiscences were translated in collaboration with my wife, Jeanette McGlamery.

Leonardo Ciampa is artistic director of organ concerts at MIT. He is a highly regarded organist, pianist, and composer.

By Omar Caputi

“Maestro, excuse me . . . but why are we tuning the whole Krummhorn if in the concert you’re using only the central octave?”

“Because every pipe has its dignity!”

This pithy reply by Massimo Nosetti would suffice to explain his personality and wisdom. Behind his impeccable daily necktie was a man of unquestionable human quality and great spirituality. In his concertizing and teaching, in his composing and organology, in his liturgical work and choral directing (and what directing he did with his prestigious chorus Cantus Firmus), he knew how to give us culture with a capital C. The Maestro was a man of sterling character, severe with himself and with his students. Without extraneous turns of phrase, he managed to exact discipline. That discipline became our art.

With his over 2,500 concerts, held on many continents, he went to great lengths to spread organ music in every direction, 360 degrees. In his concert programs, always varied and always appropriate for the instrument he was playing, his comprehensive musicality was never absent, from early music to the music of our day, with no discrimination towards repertoire, so as to bring light even to the most unknown compositions, by composers who often were intentionally “forgotten” by many in the 20th century.

This love and attention for the disclosure and the rediscovery of the great art of the organ had its apex with the realization in Torino of the prestigious Festival Organistico Internazionale di Santa Rita, a music festival in which the greatest organists of the world performed. Thanks to them, one was able to listen to so much music.

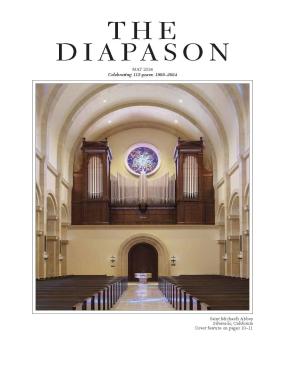

All this great music was a gift from God, as was the special pipe organ on which it was heard. Indeed, another great work conceived and realized by our Maestro: the four-manual tracker by Francesco Zanin (one of the largest and most beautiful in Italy) at the Basilica di Santa Rita, which with its almost 4,000 pipes permits the performance of a very vast repertoire.

Although he was a profound connoisseur of the philological issues and the various concepts relating to performance practice, he knew how to avoid their sterile techniques, incarnating the spirit of the Italian organists of the early 1900s—Ulisse Matthey, Marco Enrico Bossi, Pietro Yon, and Fernando Germani. I would argue that, exactly a hundred years later, Massimo Nosetti was the founder of a new “Cecilian Movement 2.0.”

Maestro, high in the heavens, may you be serene. We, your students, will continue to give dignity to every pipe and to every note!

Omar Caputi served for 27 years as Maestro Nosetti’s assistant and co-organist at the Basilica di Santa Rita in Torino and succeeded Nosetti as titular organist of the basilica.

By Michel Colin

My first contact with Massimo Nosetti was many years ago. I very much liked a piece on one of his recordings, but the score was not at all

easy to find. He sent me the score in question with a nice note attached.

We met again at a recital that he gave on the organ of the basilica in Saint-Raphaël, on the French Riviera. Thereafter, we continued our relationship though letters and phone calls, and we were able to see each other, particularly during a visit to the historic Italian organ built in 1874 by Valoncini at the church in Contes, near Nice. He brought his students at the invitation of our mutual friend, Olivier Vernet, organist of Monaco Cathedral.

The goal of these visits, other than the pleasure of seeing each other again, was to share knowledge about Italian organs among young organists in training, to encourage a musical exchange between French and Italian students, to have them discover a cultural heritage they certainly had in large quantity in their countries. But here, I was able to show an exceptional instrument that didn’t have a direct equivalent in Italy, despite its modest size. (I had been a consultant during its restoration.)

This type of exchange visit was very convivial. Each student, at whatever his or her level, could prepare some pieces, once he or she understood how the instrument worked, with its characteristic percussion stops—bass drum, little bells, cymbals—an organ adept at highlighting the “Bel Canto” (i.e., operatic-style) repertoire that was not as yet well known.

We saw each other again in Italy. A particularly wonderful memory was a special masterclass, with some of the best students from his organ studio at Cuneo Conservatory, at an exceptional organ made available to the students of the class. The plan was for me to teach the French repertoire that they knew, and the basic principles such as the interpretation of tempos, expression, and registration. Massimo thought that the students would accept this if it were a French person explaining the music of his own country. I could also amuse them with many anecdotes. The students were therefore able to experience the value of the teaching that was offered them.

I then had the luxury of explaining to them my work as an organ curator, historian, and technician. They held in their hands old documents such as the writings of Clicquot and Dom Bedos, as well as a few pipes, and even a serinette (small barrel organ). Thus they learned the rudiments of building and tuning; Massimo thought it was very important for them to have effective knowledge and practical experience of these, and the usual teaching time never permits this.

This historical, musical, and technical border-crossing seemed to Massimo and myself to be the basis of a venture in the spirit of the “chappelles” or cloistered schools (écoles cloisonnées).

Many know the wide distribution of Massimo’s discography, and his impressive repertoire, played with finesse on various instruments, always well adapted to the repertoire. He was one of those rare Italian organists to perform widely in France for many years.

Many of us will miss him for his legendary competency and kindness. We both had in common the pleasure of laughter and a sense of humor. I had fun translating his last name into French, which sounds like the favorite food of the squirrel! I once made a sketch of a lost hazelnut (noisette) on an organ keyboard, followed by the rodent’s gnawing. He thought that was very funny. Needless to say, despite his high stature, he knew how not to take himself too seriously.

We have been thinking especially about his wife and those close to him, who encouraged him in his brilliant career as an international concert and recording artist. Farewell, my friend. We will see each other in a world without suffering. We won’t forget you; your honest smile accompanies us.

Michel Colin is titular organist of the Basilica of Notre-Dame de la Victoire in St. Raphaël, professor of organ and organology at Toulon Conservatory, and consultant in ancient organs for the French Ministry of Culture.

By Olivier Vernet

I first met Massimo Nosetti many years ago. We had organized a workshop around a small Italian organ in the town of Contes, near Nice. It was an opportunity for his students from Cuneo and my students from Nice to meet each other.

The day was memorable, with Massimo sharing his kindness and his extensive experience with Italian organs. I also discovered a cultured, sensitive, amicable, and open-minded person.

When I had concerts in Italy, close to Torino, I often saw Massimo in the audience. He always had kind words. I saw him for the last time with his wife in December 2012 at a concert in Pinerolo.

He had organized a small trip to Monaco in July 2013 for friends; because I was away at that time, I was unable to show them the new instrument of the cathedral, but I had made arrangements so they could play the Dominique Thomas organ. They were thrilled.

Massimo had agreed to come and give a concert for our Festival International d’Orgue 2014. We were discussing the program he was thinking of playing . . . Unfortunately, life decided otherwise.

Massimo Nosetti was for me a wonderful person to know. I remember our mutual friendship and the moments of sharing. He was a great artist. We still have with us his numerous recordings, but we miss him greatly.

Olivier Vernet is the titular organist of Monaco Cathedral and an award-winning concert artist.

By Elia Carletto, Fabio Pietro Di Tullio, Gianfranco Luca, Tommaso Mazzoletti, Alessio Pace, Matteo Scovazzo, Carmelo Tavarnesi, and Ruben Zambon

The following is an excerpt from a tribute by Nosetti’s organ class, given at his funeral at the Basilica di Santa Rita in Torino.

Buon giorno, Maestro. Here we are. Your students. Your children.

The last time that we were all together was for your Holy Week concert last April. Such sadness we feel not seeing you seated at the console of the organ, of which you were so proud. So many times you spoke to us about it as one of your most precious creations.

How much music we made together. With your immense knowledge and noble style, you never failed to make us feel honored to serve this noble art.

Affectionate father and zealous teacher, we will miss your lessons, in which you always knew how to find the exact term, a phrase in Latin or in Greek, a word in German. Like a great gentleman you never criticized anyone; you were never jealous. You always said to us, “You mustn’t ask anything of anyone; they will come search for you. You must give honor to the organ world.”

We remember how you prepared us for our exams with a rare passion and involvement, how much effort you made to perfect our public performances. They were not mere exams, but moments in which everything was put into play.

Several of us came from faraway cities in order to study, to be able to learn as much as possible. To be your student was like attending the conservatory, doing masterclasses, competitions, and advanced classes all at the same time. You were . . . a sea of knowledge.

We thank you for the many organs in Italy that you designed, on which several of us play; you’ve given to us and to posterity the gift of instruments.

It is impossible that everything should finish here. An illness cannot erase all of this. You have hurled a rock in the lake that has created waves, which certainly will never end. We will continue to work as good professionals as you always taught us, making music and continuing to imagine the poetic things you might say to us regarding the interpretation of a work. In this way, your music will not disappear, but will live again in us.

Thank you for everything. This is not a farewell, but a till-we-meet-again. Massimo Nosetti is not dead. Music renders you immortal. You are and will be our teacher. Always.