The 16th National Choral Conference’s theme was “Rekindling Music Together: Finding Our Common Voice.” The American Boychoir, host for this conference since its inception in 1987, is an uncommon group of voices, trained and shaped year-round into one of the world’s premier choral organizations. The choir’s excellence has been a feature of and inspiration for participants of past conferences, with featured clinicians leading the choir in open rehearsals, culminating in a final concert. This year, Fernando Malvar-Ruiz, director of the American Boychoir, intentionally loosened the bolts of the choir’s former exhibitionary modus a bit as displayed in previous conferences, and allowed a special glimpse into the artistic process of the American Boychoir.

While attending a choral conference, one usually has opportunities to observe open rehearsals of a featured choir that has been thoroughly prepared in the days leading up to the conference’s opening. Featured clinicians in this instance usually deal with interpretive considerations of the repertoire and perhaps less with the processes that brought the choir to that point. The same conditions exist in the typical masterclass. Those attending at least two of the last National Choral Conferences prior to Malvar-Ruiz’s appointment as director have witnessed the American Boychoir at a typical high level of choral polish at the onset of the conferences. In planning this conference, however, Malvar-Ruiz decided to open a new chapter in the history of this conference. “If you want to hear a polished choir, you could just go to a concert,” he explained in stating his intentions for this conference. “What we are interested in is not result but process.”

So with a leap of artistic faith, the 16th National Choral Conference afforded participants the rare opportunity to witness in open rehearsals the choir in a state of process towards final result. The repertoire selected for the conference was still in varying states of progress, according to Malvar-Ruiz, who admitted to attendees of the conference prior to the first open rehearsal that the boys were “a little nervous.” Open rehearsals are not new to the choir—choir rehearsals are open to prospective families who are considering their boys for the school. Open rehearsals of the sort described above on the national stage, however, represent a new philosophy for the conference.

For some choral directors, it would have been easier to have pulled thoroughly prepared works from off the shelf. Instead, participants of this conference were offered something more. After signaling to the choir that the rehearsal was to begin, Malvar-Ruiz wasted no time in outlining his objectives. “Here are my goals for these pages, boys: good diction, great phrasing, great tone.” Malvar-Ruiz in rehearsal operates with ease and camaraderie with the boys, yet firmly remains on task in achieving the goals set before the choir. It is a unique equilibrium between ease and objective that makes for a buoyant atmosphere within his rehearsals.

Malvar-Ruiz was appointed Litton-Lodal Music Director of the American Boychoir in July 2004. Since then, he has toured with the choir to 30 states and Canada. A widely sought-after guest conductor, lecturer and clinician, Malvar-Ruiz served as artistic director and guest conductor for the 2005 World Children’s Choir Festival in Hong Kong. He is a native of Spain with degrees from the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música in Madrid and Ohio State University.

Malvar-Ruiz compares his first opportunity conducting the American Boychoir (then under the leadership of Jim Litton) to being “handed the keys to a Ferrari.” Participants at this conference had the opportunity to hear “the Ferrari” in the garage with its hood up. The “garage” for this occasion was the Main Hall of Albemarle, the former Georgian mansion and summer home of pharmaceutical giant Gerard B. Lambert of Listerine® fame, and now home of the American Boychoir School. The acoustical intimacy and proximity of choir to audience made for an ideal setting for Malvar-Ruiz’s approach.

At one point during the rehearsal, Malvar-Ruiz had the choir sing a vocal line in imitation of individual orchestral instruments in order to determine what overall timbre would be best suited for the work. At times, the Ferrari’s performance did not possess its usual finesse; yet for those interested in how artistic ends are met, this modus of rehearsal was informative, at times even intriguing. Busy at work with the choir, Malvar-Ruiz was not the least apologetic in publicly tuning up his Ferrari—he seemed to relish the opportunity. In fact, he was already anticipating this new approach at the conclusion of the last conference held on the campus of the University of New Jersey in Ewing when he was the associate music director of the American Boychoir (see “The 15th National Choral Conference,” The Diapason, January 2004). According to Robert Rund, President of the American Boychoir School, there was a desire for the present conference to dissolve professional barriers and allow for the confirmation that there are more similarities among the work of those in the profession than differences. “We knew it was going to be a different National Choral Conference than we ever produced,” Rund said. “We run the risk of being the elitist choir . . . we’re all going through some kind of process and I think we can share commonalities regardless of what one’s product ultimately is.”

Similar to the last conference, “interest sessions” were offered dealing with different areas in the profession. For the last two conferences, participants had to choose between some offerings at the expense of others, a difficult task, owing to their informative content. This year, however, the schedule was arranged so that all sessions would be available. The topics included “Making an audition tape,” “Teaching across the curriculum,” “Sure-fire warmups,” and “Developing the changing voice.”

A keynote address was offered on each day of the conference. On day one, Dr. Judy Bowers of Florida State University spoke on “Advocacy for Music,” in which she traced the history of choral music in America up to the present, along with her convictions concerning choral advocacy in what was for many of the participants a lively, informative, and at times entertaining address.

Dr. Helen Kemp, Professor Emerita of Westminster Choir College, delivered the second keynote address, “Children’s Choirs: Commonality within diversity,” espousing her philosophies of “body, mind, spirit, voice: it takes the whole person to sing and rejoice.” An artist held in tremendous affection by many in the choral world, Kemp’s remarks represented the result of seventy-plus years in the profession, spanning the evolutionary periods of 20th-century American choral music.

Dr. Anton E. Armstrong of St. Olaf College is no stranger to the National Choral Conference, having been a featured clinician in the 14th conference as well as an alumnus of the American Boychoir School. “I’ve always said it—this is what lit my fire for choral singing,” says Armstrong in describing his experience as an upperclassman in the school. Participants of this conference did not have the opportunity to observe Dr. Armstrong lead the American Boychoir in rehearsal as at the 14th conference, which perhaps represents a watershed in the history of the conference (see Robert E. Frye’s documentary “Body, Mind, Spirit, Voice,” www.americanboychoir.org).

Conference participants themselves were led by Dr. Armstrong in a reading session of select choral repertoire. In addition, Dr. Bowers and Dr. Kemp participated in these sessions. It is remarkable to observe how contrasting choral directors achieve their results at the podium, especially when the works under consideration are to be read only once, usually in quick succession. In the quiet authority of Dr. Armstrong, the almost uncontainable energy of Dr. Bowers, or the sheer radiance of Dr. Kemp (who could perhaps conduct entirely with her facial expression alone if made to), participants were exposed to contrasting conducting styles and philosophies as well as a diverse cross-section of choral music.

Fred Meads, a recent addition to the American Boychoir staff, is head of vocal pedagogy. From him the boys now receive individual instruction in voice in addition to their regular choir rehearsals. A pedagogical technique of his was demonstrated in the interest session “surefire warm-ups” led by Malvar-Ruiz. In this session, boys from the school demonstrated some of their vocal warm-ups in conjunction with the use of individual hand-held mirrors. The mirrors are used to confirm visually if proper positions of the mouth are being used in order to produce the desired sound. American Boychoir accompanist and assistant director of music Dr. Kerry Heimann served as congenial accompanist and master of ceremonies throughout the conference.

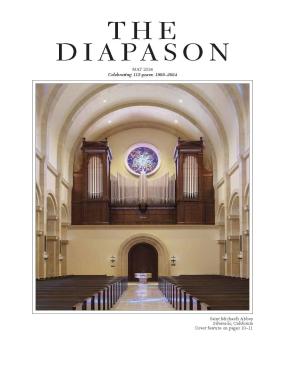

If this conference was concerned with process, then naturally the final concert would be concerned with result. The results were heard in the acoustically opulent Miller Chapel on the campus of Princeton Seminary, an ideal “sonic frame” in which to set off the culmination of the choir’s work. In his greeting to the audience, Malvar-Ruiz began, “We almost have a choir.” Despite his remark, the audience did have a choir and the choir did not disappoint. For artistic process to be capable of arriving at the definitive desired objective is debatable. Yet for some, the journey is what makes the trip worthwhile and not necessarily the final destination itself.

Malvar-Ruiz describes the typical choral concert as merely being “a collection of songs” and wishes to expand beyond a model that in his opinion has run its course. “The next big step in my development as a musician is to embrace the paradigm of a choral ensemble in a 21st-century reality, a 21st-century society, a 21st-century culture. It’s a wonderful challenge.” It is a challenge that will certainly result in new processes and a new journey.